We have some pretty remarkable people who work at INL. Included in that batch of people are our colleagues with disabilities. In many cases, their disabilities are invisible to the naked eye, so we don’t even know they have one. Other disabilities are more visible. Someone who has lived with a disability their whole life may have a different outlook and perspective than a person who develops a disability later in life.

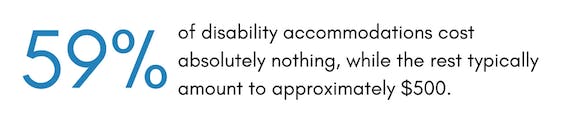

Many myths exist about having employees with disabilities in the workplace. One of the biggest is that it’s expensive to accommodate a person with a disability. The reality: according to a 2017 report by the Job Accommodation Network (JAN), a service of the Office of Disability Employment Policy of the U.S. Department of Labor, “59 percent of disability accommodations cost absolutely nothing, while the rest typically amount to approximately $500.”

In fact, the benefits of making accommodations significantly outweigh the minimal costs. The JAN report found numerous direct benefits of providing accommodations to employees with disabilities, including:

- The company retained a valued employee.

- The employee’s productivity increased.

- There was no cost to hire and train a new employee.

Several indirect benefits also result. These include better collaboration with colleagues, increased overall company morale, and increased overall company productivity. There is definitely a business case for employing and accommodating people with disabilities.

“People with disabilities are welcomed and embraced at INL,” said INL Director Mark Peters. “We want to ensure all our employees feel welcome and valued. Hiring employees with diverse abilities strengthens our laboratory, and enables and drives great science and innovation.”

What’s it like to live every day with a disability? What kinds of things do people with disabilities deal with that those who don’t have a disability might never consider? Two employees share their stories and help us see, “I’m different, like you.”

Drake Kirkham

Drake Kirkham is a quality manager in the Radioisotope Power Systems Program at the Materials and Fuels Complex (MFC). The program builds, tests, stores, and delivers plutonium-fueled electrical power systems for use in space missions, most notably the Mars Science Laboratory rover Curiosity, now operating on the Red Planet, and the Pluto/New Horizons probe.

Kirkham loves his job, particularly because he sees a direct connection to what he does and the INL mission, and knows what he does makes a huge impact on the world. “The Voyager probe uses the same type of nuclear power source we (INL) use today and it’s been operating in space for over 35 years! We’re the only ones in the world who can do what we do,” Kirkham said.

He also has vast experience in sport rocketry. Kirkham was a certified Level 2 High Power Rocketry flyer, which means he was authorized through the National Association of Rocketry to launch rockets up to a certain altitude. “I’ve launched rockets up to 9,000 feet and recovered them to fly again,” he said.

Eleven years ago, after noticing some loss of feeling in his fingertips and starting to get tired faster than normal, Kirkham was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis (MS). The disease progressed slowly for five years with little effect, then suddenly, began progressing quickly.

“In one year, I went from using a cane, to a walker, and finally a power wheelchair,” said Kirkham. He now uses a wheelchair 100 percent of the time, but because of the accommodations INL has provided, he has been able to continue to perform his job and work at the desert Site.

Some of the accommodations at MFC include voice-recognition capabilities, being able to telecommute when needed, and modifications to restrooms. For instance, the restroom in his building was modified with two sets of automatic doors to allow safe ingress and egress.

When certain areas of MFC have be remodeled or upgraded, Kirkham was contacted to make sure accessibility was taken into account. “When Security upgraded the security gate equipment at MFC, my wheelchair was measured and an accessible lane was included in the upgrade,” he said. “I no longer have to worry about scraping the sides of the detectors as I pass through them. I also have my own Emergency Evacuation Plan in case something happens.”

Kirkham said he has some great colleagues at MFC. “Two of my co-workers who live near me in Rexburg pick me up and drive me to and from MFC in my special van each workday.”

Colleagues can do simple things to assist those with disabilities. One of the easiest things is just to be aware that not all meeting or training rooms are easily accessible and that a person with a disability might need more advance notice to plan for transportation.

Kirkham said although he has some physical constraints, ultimately, he’s just like any other employee at INL. “I’m not contagious,” he said. “So the best thing people can do is treat me like a normal person. If I need help, I’ll ask.”

Dale Kepler

Dale Kepler is a mechanical engineer at the Advanced Test Reactor (ATR) Complex. He is leading the Core Internal Change-out (CIC) engineering team, preparing the reactor for the CIC in 2020.

A 27-year veteran of INL, Kepler started at Argonne in 1990. He worked as a drafter for his first 20 years at INL, then took advantage of the Employee Education Program and went back to school to finish his degree. In 2010, he received a Bachelor of Science in mechanical engineering from Idaho State University.

Kepler says he loves being at the ATR Complex. “I like the solid commitments and deadlines I have to meet to run an operating facility,” he said. “What better place to be than a nuclear facility in the desert where we have a solid mission? I get to be an engineer and sit 300 feet from an operating reactor.”

Kepler said few people get to do a job they really like at such a unique facility. “Engineers get paid to think. It’s great,” he said. Although diagnosed with a degenerative nerve disease called Charcot-Marie-Tooth (CMT) at the age of 6, his disability hasn’t stopped him from working at a job he likes in such a remote location.

He worked hard just to be average at sports when he was growing up. It wasn’t until 1998 that he needed to get his first orthotics to correct a drop in both of his feet that was causing him to trip. The disease has progressed over the years. In 2006, Kepler started using a cane to help with balance. He said getting the cane was the hardest transition for him because everyone could actually see he had a disability. “All of a sudden it was apparent — now I was a person with a disability. People would run ahead to open doors for me. I had to swallow my pride and ego and say ‘thank you,’” he said.

Today, Kepler has leg braces and has trained his body to adjust to walk with the aid of a walker, however, he is numb from his toes to thighs and his fingers to shoulders.

Anyone who has visited the ATR Complex or has had to make the hot walk in the summer or frigid walk in the winter from the guardhouse to their work building knows it is difficult on even the best days. Kepler and his colleagues have found easy and creative ways to cope with navigating the expansive, 86-acre complex.

“I have an electric car that looks like a snowball and an electric scooter to help me get around. I can put my walker on the back of the scooter and get around inside buildings. If I have meetings in other buildings, a colleague and I will travel in my electric car,” he said.

Although it has taken some time to work through it, Kepler said he is now comfortable with his disability. He said people not living with a disability probably don’t realize the small things that make life easier.

“How great is life when you can wake up, get dressed fast, put your shoes on quick? It takes me probably 30 minutes just to get my braces all set up and on right. It’s a process for me to get up out of bed in the morning,” he said.

Even the simple task of going down the hall to another cubicle to talk to someone is something he no longer takes for granted. “I find myself mentally preparing for the exertion it takes to get there – thinking about where my legs are every time I step – my mind is really focused. I watch people – not even thinking about it – walking and talking. People aren’t aware of the physical and mental process I go through every day just to get to work and move around and function.” Kepler hopes that sharing these observations will help people who don’t have disabilities appreciate the small things in life.

So, what can people do to make INL more inclusive for colleagues with disabilities? Kepler says the key is to be authentic.

“We’re not all the same, but, ‘I’m different, like you.’ I’m different, and it’s OK, but I am just like you as an engineer – I’m just like one of you. We all have differences and we all have similarities,” Kepler said.

He also said people with disabilities don’t want to be treated differently than anyone else, but at the same time, they do have things they need help with. “It takes a lot of humility to get help doing simple things, but people around here at INL just want to help,” said Kepler. “The most important thing to do when you see someone who is not like you is to just communicate and talk more. Just say ‘hi.’”

Resources:

ADA interactive timeline

Department of Labor National Disability Employment Awareness Month website

Job Accommodation Network report

Paralympian Bonnie St. John: Normal is Overrated – Aim Higher (video)