Charlyne Smith’s grandfather wanted her to be the prime minister of her native Jamaica. She has bigger dreams: to solve the world’s climate crisis using nuclear energy, beginning in her home country.

“I want to build a nuclear energy infrastructure in Jamaica,” said Smith, a distinguished postdoctoral associate at Idaho National Laboratory’s Irradiated Fuels and Materials program.

She is also working on a proposal for a summer engineering program. Her goal is to expose Jamaican high school students to engineering disciplines that are not taught anywhere in the Caribbean — for example nuclear engineering, materials science engineering, and environmental engineering. She is working with the University of Florida and the University of West Indies Mona in Kingston where Jamaica operates the Caribbean’s only nuclear reactor. The 20-kilowatt SLOWPOKE-2 research reactor is used for environmental, agriculture and health studies research.

Smith, a native of St. Catherine, Jamaica, grew up with constant power outages, particularly during hurricane season.

Things would get bad when there were extreme weather events. “I remember my mother running to the grocery store with all four children behind her in a panic,” she said.

Smith’s mother would stock up on dry goods, batteries, flashlights, and candles. They would cook all the frozen items “to minimize the amount of food that would go to waste when we would lose power,” she said. They also would fill up as many pans and buckets with water because they never knew when the water supply would be restored.

Hurricane Ivan was the worst.

Smith was 9 years old at the time but recalled a three-month period when the country was without power.

It wasn’t until high school when she really understood the importance of reliable access to electricity. Her country’s lack of infrastructure became apparent during occasional visits to the United States.

“There was hot water coming out of the pipes. There were washing machines, dryers and dishwashers. All this stuff that saves time and makes life so much easier,” she said. “After my visits, I would go back to Jamaica and think there are infrastructure problems to tackle. At that point as a 14-year-old I thought the necessary solutions would come from science and engineering fields.”

At 17, she moved to Maryland, attended Coppin State University in Baltimore and graduated in 2017 with a degree in mathematics and chemistry. While at Coppin, she studied solar power but decided to pursue a doctorate in nuclear engineering after talking with a nuclear scientist. “I wanted to work on an energy solution that would have a significant, immediate, and positive impact on a nation’s infrastructure,” she said. “A solution that had the potential to replace the baseload fossil fuel energy source used in the Caribbean.”

Imported fossil fuel energy sources make up more than 87% of the energy produced in the Caribbean.

She decided while in graduate school at the University of Florida to focus on understanding fuel performance under irradiation for qualifying nuclear fuels for commercial and research use. She earned her doctorate in June 2021 and became active in pro-nuclear nonprofit groups like Students for Nuclear and Generation Atomic.

For the past three months, the 26-year-old has been INL’s Glenn T. Seaborg Distinguished Postdoctoral Associate, examining the types of fuels used in nuclear reactors. “I want my experience at INL to broaden my network and push me in the direction of my own personal career goals to achieve net-zero targets and address energy poverty, especially during extreme events,” she said. “I believe nuclear energy is the solution.”

She is doing this through science and activism.

Dennis Keiser, directorate fellow of Nuclear Science and Technology’s Nuclear Fuels and Materials Division, is Smith’s project manager and mentor. “Charlyne is one of the smartest, most driven students I have ever had the pleasure of working with,” he said.

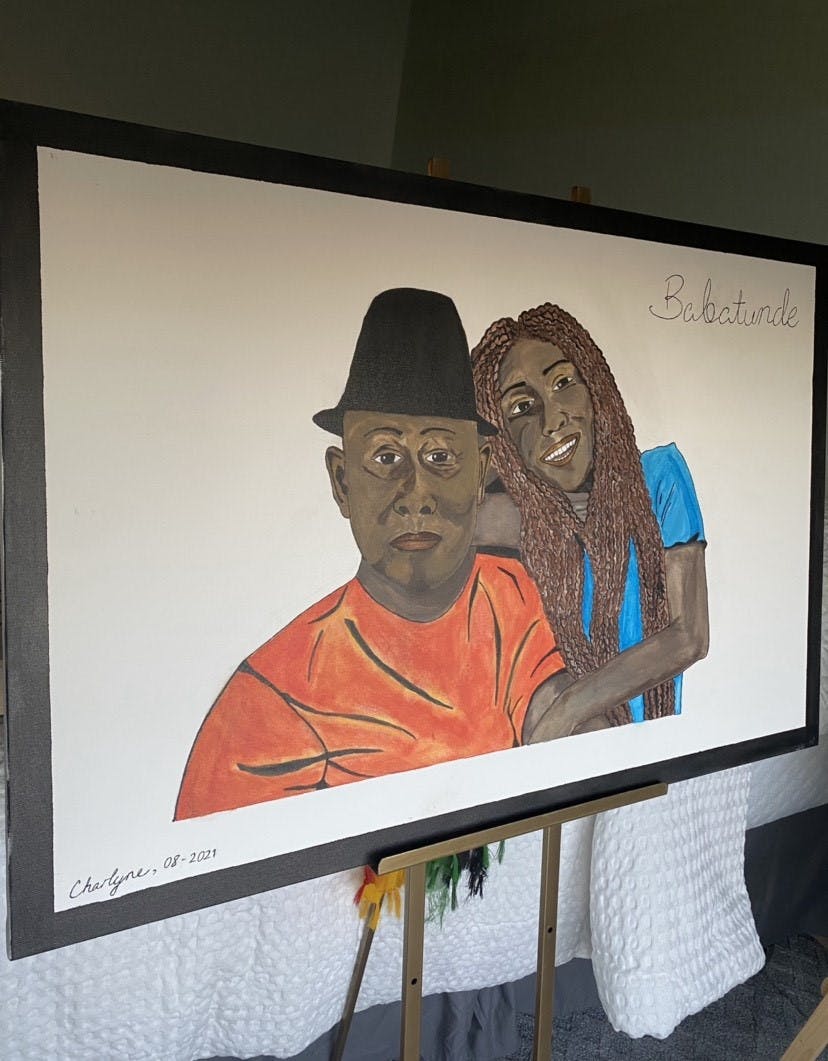

Over the course of her still-short career her grandfather still prodded her to become prime minister of Jamaica. It wasn’t until a recent visit that her grandfather finally understood her bigger dreams.

“I was telling my grandfather about my plans and he finally seemed to get onboard with the whole nuclear engineering role. He said, ‘Oh yeah, you can go and talk to the prime minister about it.’ “

So, Smith drove herself to the prime minister’s office, where she was confronted by three heavily armed security men. She didn’t get to see the prime minister but drove away with his contact information.

Her grandfather, who died 18 days after she graduated with her doctorate in August, was her biggest motivator, she said. She painted a portrait of him with her. “Those were some of my last moments with him,” she said. “He was the cheerleader who had my back and always believed that I would help to change the world for the better.”