For one eastern Idaho family, Idaho’s national laboratory provided a livable income while dad was in college, a career ladder for mom and a profession for their son that didn’t drive him out of state.

RoseMarie (Peterson) Doxey, retired since 2001, put in 38 years at various locations on the Idaho desert and in town. Her son, Bert Creasey, first hired as a security guard in 1981, now supports the lab’s National & Homeland Security Infrastructure Assurance & Analysis mission as a publications lead. The two of them have worked more combined years than Idaho’s 70-year-old national laboratory has been in existence.

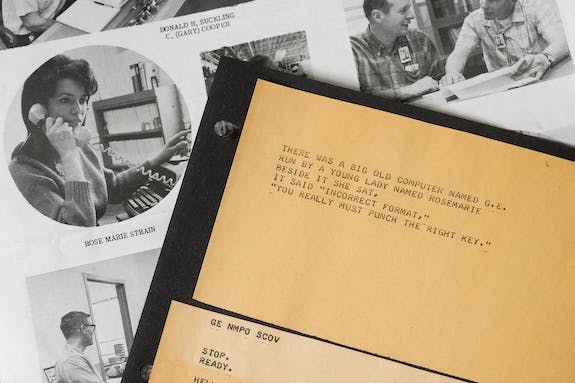

When Doxey started at the lab in 1963, it was a much different world for women who wanted to work. At the National Reactor Testing Station, as it was then called, the opportunities were secretarial or administrative. Doxey would get to see the range of opportunities expand in her career, but at the time her concerns were more immediate and practical.

As mother of two (Bert and his sister, Tami), with a husband in college, she had been working for a finance company for $225 a month. That didn’t go very far, and the economic advantages of working at NRTS were already well known. “I said, ‘I’ve got to go to the site,’” she said.

Looking back, she says she went as far at the site as a woman without a college education could go. Even more important were the extraordinary people she met and worked for.

The nation may have been reeling from John F. Kennedy’s assassination the previous Friday, but on Nov. 25, 1963, Doxey joined the steno pool at the “Tar Paper Palace,” a building left over from the construction of the Engineering Test Reactor (ETR). True to its nickname, it was a wood frame building with tar paper on the outside and cement or wooden floors. It was cold in the winter and hot in the summer. “We had a family of cats to control the mice, but nothing to control the spiders, scorpions or snakes,” she said.

If the accommodations were primitive, the daily bus ride was just as rough. “It was a learning experience,” she said. “The roads were not good and the buses were not good.”

Because she was near last on the bus pickup route, Doxey often found herself riding on one of the wheel wells, near the card players in the back, all of whom were smokers. The only ventilation option was to open a window, which was something one didn’t want to do in the winter. In cold weather, “My coat would freeze to the window and window frame,” she said.

The greatest adventure of her bus riding days came when an 18-wheeler jackknifed on U.S. 20, holding up a line of town-bound buses and vehicles for hours. INL buses then didn’t have lavatories. During this long wait on the desert, when nature called, the only option was a trip out into the sagebrush. For the three women on her bus, special arrangements had to be made for modesty’s sake.

Among the men, the crisis was tobacco-related. Before the end of the ordeal, those who had cigarettes were selling smoke for $1 a drag.

In May 1965, she transferred to join the team working on the Mobile Low-Power Reactor (ML-1), a portable reactor being developed for the U.S. Army. The project was cancelled, however, and Doxey had the choice of working for General Electric at Test Area North or at the Naval Reactors Facility.

She chose GE, and was glad for it. The manager, John Morfitt, was the best boss she ever worked for. “GE had less than 50 employees, and we were like a big happy family,” she said.

Because of her two children, Doxey opted in 1971 for a job that kept her in town, working for Dr. Jay Kunze, manager of reactor physics. Kunze became interested in alternative energy and helped start a pilot geothermal project at Raft River. Doxey graduated to project control representative, then site functions administrator, handling public relations for the Raft River project as well as the logistics. By 1978, she was a senior administrator and working for Morfitt again, handling conference planning, management and analysis for the site’s Small Hydro Project, traveling extensively around the United States. She followed Morfitt to the Science and Technology Department when he became division director.

In the 1980s, Doxey was a senior buyer for seven years, and at the end of the decade, she was back at TRA as principal communications specialist for Reactor Safety Analysis. “Things had really changed at TRA,” she said. “Buses had definitely improved – no wheel wells, true air conditioning, better heat, no smoking allowed,” she said. As a principal business/operations specialist, she worked from 1990 until her retirement for the Environmental Restoration Program.

Growing up all this time, Bert, born in 1960, says he had an awareness of the site, but his ambition was to be an architect. He took drafting courses in high school and at Ricks College, but had second thoughts when his adviser told him that he’d need to move to the coast if he wanted to pursue a real career in that field. It was then that he turned his attention to opportunities at the site.

By 1981, he was following in his mother’s bus tracks, first working as a security guard for American Protective Services, Inc., the site’s security contractor. He advanced to security inspector, then served as a sergeant at the Idaho Chemical Processing Plant. Moving up the managerial chain, he left in 1988 to work for Westinghouse at DOE’s Savannah River Site, then returned to Idaho in 1991 to continue working for Westinghouse.

The site’s National and Homeland Security mission has continued to grow. Creasey was in the Willow Creek Building on Sept. 11, 2001, the day of the terrorist attacks on the Pentagon and World Trade Center buildings. “Security tightened up a lot more right after that,” he said.

As the lab has been a constant thread through their lives, mother and son see their work at the lab as important service to their country. “We both got to do our part,” said Creasey. “No matter what our role is, we all work together as a team to meet the lab’s mission and move the country forward.”

“I feel like we have contributed a lot to the U.S.” said Doxey.