History has a way of sneaking up on a person. In Cuyler Cameron’s case, it was in the summer of 2022, when he was on a road trip from Colorado to Oregon. Westbound on U.S. Highway 20, he saw the Idaho National Laboratory sign, which made him think immediately of his grandfather, Reid Anderson Cameron Jr., who worked for INL in the days when it was the Atomic Energy Commission’s National Reactor Testing Station.

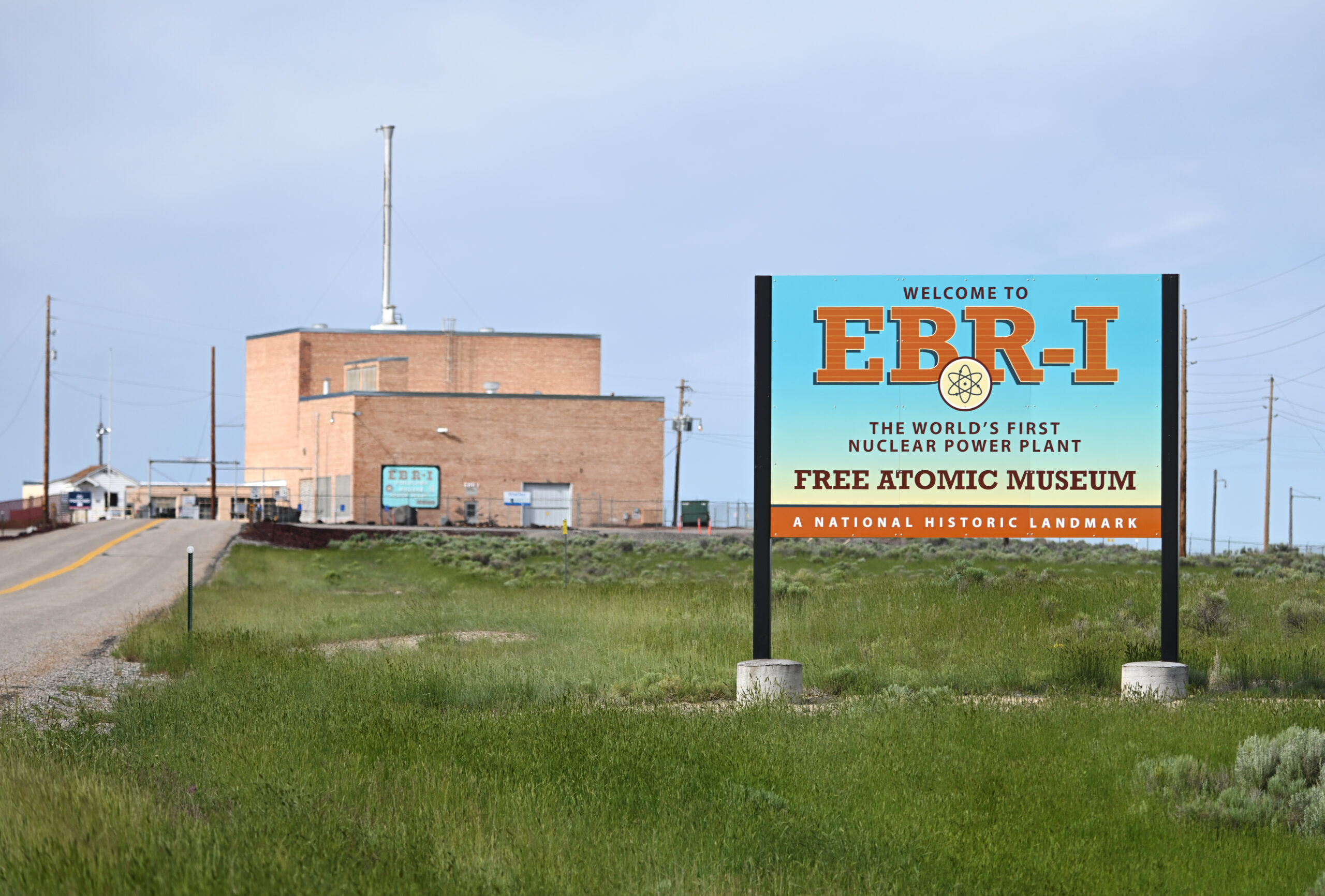

“He was quite proud of it,” Cuyler said. Not much later, when he saw the sign for Experimental Breeder Reactor No. 1, he knew he had to stop. A popular tourist attraction between Idaho Falls and Arco, EBR-I is where nuclear energy was harnessed for the first time to create electricity. That happened on Dec. 20, 1951, when the reactor, turbine and generator lit four 200-watt lightbulbs on a strand of wire.

If he’d known what he was in for, Cuyler said he would have made a pilgrimage a lot sooner. Right on the wall, written in chalk and now protected by plexiglass, was “R. Cameron,” one of the 16 physicists, engineers and chemists who took EBR-I live. “I was a bit in awe, having heard the stories,” he said. “I felt such a presence of the past that I had a smile plastered on my face the whole time I was there.”

What resonated even more than his grandfather’s name was the little Aeolian doodle at the top, drawn by his grandfather and inspired by former Argonne National Laboratory Director Walter Zinn’s saying, “If a man can whistle, he can generate steam.” Having spent a lot of time with his grandfather while growing up, Cuyler, now 43, said he had seen plenty of doodles like that.

As great a monument as EBR-I is to American ingenuity and innovation, what impressed Cuyler most about the place was its simplicity. The people who built it knew what they were after: a liquid metal-cooled reactor that could create more fuel than it consumed. Its purpose was to create plutonium-239 for the Atomic Energy Commission (which it did in 1953). But its generation of usable electricity paved the way for others to build on its success.

Simplicity was one of Reid Cameron’s top qualities, Cuyler said. “He was a loving, caring gentleman who had an immense curiosity for the inner workings of things.”

Born in 1921, Reid Cameron enlisted in the U.S. Army after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. His engineering skills landed him a job with the Manhattan Project. At Los Alamos, he met his wife, Helen, a chemist. The two went AWOL to tie the knot then kept it secret until after the war, when they had their official wedding in 1946.

After his discharge, Reid Cameron attended Illinois Institute of Technology then started working for Argonne National Laboratory. In April 1951, with EBR-I nearing completion, he came west with three colleagues – Bernard Cerutti, Leonard Koch and George Kirby Whitham – to help start up the reactor.

During their time in Idaho Falls, Reid and Helen had two children: Mercedes, in 1952, and Reid III, in 1954. Fluent in Spanish as well as English, he was hired by General Electric to manage reactor outages all over the world. Leaving their kids stateside to attend school, he and Helen lived and worked in India, Japan, Taiwan and Spain. When retirement came, they settled in Grand Junction, Colorado. Altogether, they were married 70 years. Helen died in 2015 while Reid passed away in 2019 at age 98, the last of the men on EBR-I’s wall to go.

With its austere architecture, huge pipes and deep foundation in the lava rock of the Snake River Plain, there are few places in the world like EBR-I. Declared a National Historic Landmark by President Lyndon Johnson in 1966, the “atomic museum” attracts thousands of visitors every year between Memorial Day and Labor Day.

While on one level it might be a relic of the early Atomic Age, at a deeper level it is a living monument to people like Reid Cameron, who had the freedom to apply their gifts and build something truly unique and amazing.