Nuclear engineer Kemal Pasamehmetoglu remembers when blackouts darkened his childhood home in Istanbul, Turkey.

Two or three times a week, power outages forced Pasamehmetoglu’s family to go without running water, and he and his younger sister had to study by candlelight.

Even when the lights were on, the rudimentary coal-fired power plants that provided Istanbul with electricity choked the city with pollution.

“In wintertime, the minute you got out on the street you could smell the sulfur in the air,” said Pasamehmetoglu, a senior researcher and Versatile Test Reactor director at Idaho National Laboratory. “You could barely see 50 yards in front of you.”

In the United States, these conditions—no electricity, no water and severe pollution—are usually associated with poverty, yet Pasamehmetoglu’s parents were well-educated and employed. His father was deputy director of the Central Bank in Turkey and his mother worked as a chemist, and later, a teacher.

Still, Istanbul’s rapid growth coupled with its unstable electrical grid regularly plunged Pasamehmetoglu and his family into third-world living conditions.

In the ’70s, Pasamehmetoglu was one of the majority of people across the globe without access to reliable, affordable, clean power.

Today, researchers estimate that more than 1 billion people lack access to electricity altogether, and many billions more lack access to reliable, clean power. Those billions suffer higher mortality rates and a lower standard of living as a result, Pasamehmetoglu said. And in the quest to provide that energy, nations, especially impoverished ones, historically have opted for power sources that are cheap and easy to build as opposed to being clean.

As his nuclear engineering career advanced, Pasamehmetoglu kept in mind that lesson from his childhood: Energy access is about more than the ability to power a flat-screen TV or charge a cellphone, it’s about human rights and the future of the planet.

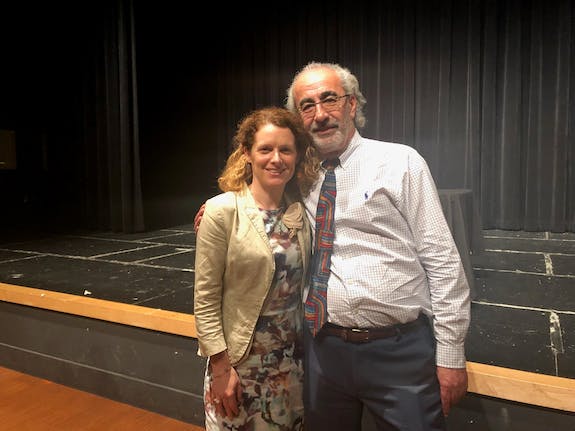

That’s why Pasamehmetoglu has teamed up with a seemingly strange ally — Kirsty Gogan, a London-based environmental advocate.

Gogan, through her work in Romania and India, has come to many of the same conclusions as Pasamehmetoglu about energy, the human condition and the environment.

Finding a sustainable balance

Pasamehmetoglu and Gogan have developed Eco:Logic, an effort to foster discussions and address what they believe is the world’s most challenging equation – finding a sustainable balance among humans, technology and the environment.

They want to move past polarized discussions on energy and have genuine conversations about how to provide electricity to the world’s citizens while also reducing carbon emissions. They believe this polarization has prevented people from really considering all of the clean energy options available.

“A lot of this discourse is very tribal,” Gogan said. “We form our ideas about things based on our sense of belonging. We’re not rational creatures. Kemal had this deep value-based approach in his thinking, which makes him unusual and helps him connect with people that may not belong to a nuclear engineering tribe.”

Pasamehmetoglu said his interest in increasing energy production and Gogan’s interest in reducing carbon emissions intersect because of shared values about human rights and the environment.

“Let’s not turn this debate into a technology debate,” he said. “Let’s turn it into a debate about values. Let’s talk about the performance, cost, reliability and how much environmental impact we create by our choices, with the understanding that all of these technologies have an impact on the environment.”

Pasamehmetoglu and Gogan are planning a speaking tour centered around this concept, their own energy experiences, and how they have arrived at their current views of energy.

A very different childhood

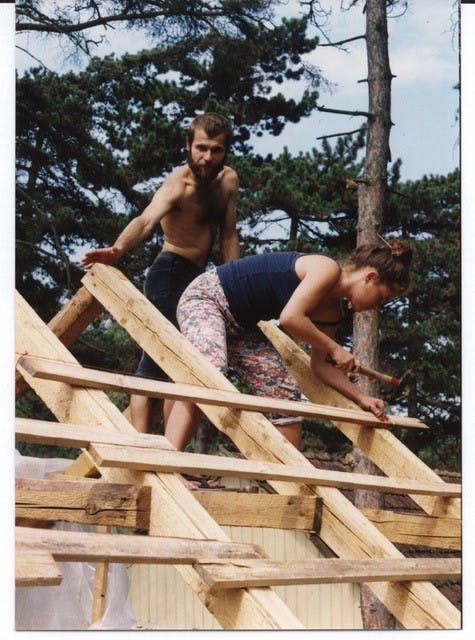

Growing up in the British Isles, Gogan experienced a very different childhood than Pasamehmetoglu.

She was born in Ireland, the daughter of a stay-at-home mother and a salesman, but her family moved to London when she was 10.

Gogan credits her father’s interest in politics and in helping homeless youths for sparking her career as a political activist.

As a child, she was a member of the World Wide Fund for Nature and Greenpeace. She became a vegetarian at age 10, and grew up inundated with literature about rainforests and pandas.

In the early ’90s, while Gogan was still a student, she participated in a youth movement called “Reclaim the Streets” that focused on social and environmental justice.

“We could see that environmental damage was impacting the poorest people first,” she said.

After graduating from college, Gogan spent a year working in Romania for European Youth for Action. There, she regularly visited a friend’s home in Transylvania where the family lived an agrarian lifestyle.

“It was a real subsistence farming kind of life in these mountains,” she said. “They don’t have a bin in their house because every single thing is used. They would keep chickens and a pig and all the scraps would go to those animals.”

But it was watching her friend’s mother wash the family’s clothes by hand that left the biggest impression.

“She would heat the water on the stove and hand wash everything,” Gogan said. “It was such backbreaking, laborious work.”

Empowering people through access to electricity

Gogan saw firsthand how profoundly the absence of electricity—or, in this case, a modern convenience powered by electricity—could impact someone’s life. It’s more than eliminating a chore, it’s about empowering people, women in particular, by giving them the free time to do more important, fulfilling work.

“When I went back to UK and got my first proper job, the first thing I did was go buy her a washing machine,” Gogan said.

Her next assignment took her to India. There, she experienced a country where the social impacts of a lack of clean, reliable energy were compounded by extreme poverty, overpopulation and pollution.

In many cases, “living in poverty is really bad for the environment,” Gogan said. “If you’re cutting down trees because you have to burn wood, for example, or are burning dung or some other kind of smoky fuel.”

“Access to energy is fundamental to our quality of life and our freedom to do productive work and to be healthy and safe and secure,” continued Gogan, who is now co-founder and executive director of the environmental nonprofit Energy for Humanity. “It’s all unlocked by having access to energy.”

Humanity’s most important challenge

For Gogan and Pasamehmetoglu, providing that access for the estimated 10 billion people who will inhabit the planet by the year 2050, while simultaneously protecting the planet’s ecosystems, is perhaps the most important challenge facing humanity.

Coming up with a solution to that challenge will need to involve more than just intermittent sources of renewable energy such as wind and solar. Nuclear energy will undoubtedly be part of the mix, say both Gogan and Pasamehmetoglu.

The advent of new, safer reactor designs that produce less waste makes a strong case for using the carbon-free, energy-dense technology in tandem with renewables like solar, wind, geothermal and bioenergy, Pasamehmetoglu said.

“We have to think about not only what we need here, but also what kinds of reactors we need in other parts of the world where the safety and security culture is not quite as mature,” he said.

An awakening to benefits of nuclear power

Gogan is part of an awakening by many environmentalists to nuclear energy’s importance as a safe, carbon-free energy source for the future.

“As an environmentalist, I was, by default, anti-nuclear,” she said. “And here I am now with an environmental NGO advocating for nuclear as a solution. Twenty years ago, I wouldn’t have believed you if you’d told me that this is what I would be doing.”

In developing nations, especially, fossil fuels will continue to play an important role, said Pasamehmetoglu. Accepting the reality of fossil fuels and using technologies to reduce their impacts will be a major step in securing the planet’s energy future.

“We need to figure out carbon capture and sequestration or reuse,” Pasamehmetoglu said. “There has been a lot of progress made in the last four to five years. I think it’s almost ready to be deployed at a large scale.”

Through Eco:Logic, Pasamehmetoglu and Gogan hope to foster discussions with different communities on their terms, speaking through their values, about finding the right mix of energy sources.

“Part of the solution is communicating to people that there is no silver bullet, that we need everything in the mix,” Pasamehmetoglu said.

For more information, visit: energyecologic.org.