From Frederick Douglass, to Harriet Tubman, to Sojourner Truth, to Claudette Colvin, to Dr. Martin Luther King, black people have always made history and continue to do so today. During the month of February, the United States recognizes Black History Month as a way to celebrate the achievements of blacks and their phenomenal contributions to our society.

INL’s multicultural workforce draws the best and brightest talent from all over the world. Designations like Black History Month provide opportunities to raise cultural awareness and to encourage discussions about issues impacting people and society. Why does INL care about inclusive diversity recognitions? Because organizations that embrace inclusive diversity deliver better results. They have happier, more collaborative, psychologically safe employees. When employees feel a sense of belonging, they are less distracted by uncertainty and interpersonal conflict and can put all their energy towards the task at hand. This enhances organizational outcomes and increases their individual opportunities for career advancement. In other words, when our laboratory experiences growth, employees experience growth too.

This month, three INL employees share their experiences moving to Idaho, and why they chose to work at our world-changing laboratory.

Meet Emmanuel Ohene Opare

Emmanuel Ohene Opare is a systems engineer who first started at INL in 2008, left to work on an edupreneurship project in Ghana in 2012, then returned again in 2017. As a systems engineer, he looks at the technical details of a project, assesses how the parts interact with each other, and enables the success of the project. It’s a job where he gets to balance political, social and technical aspects, and then pulls them together so the project succeeds.

Ohene Opare has a bachelor’s degree in mechanical engineering and a master’s degree in engineering management. Originally from Ghana in Western Africa, Ohene Opare describes his native country as very diverse and filled with people of different ethnic, religious and cultural backgrounds. Ghana has a population of about 27 million people and is roughly the size of the state of Oregon.

Ohene Opare said Ghana is known as a “beacon of democracy” and has many similarities to the U.S., including its fight from the British for independence and having people from different cultures, religions and ethnicities.

How did a young man from Ghana end up in Idaho? “I’d always wanted to work for an institution that makes a difference in the world, that makes the world a better place,” Ohene Opare said. “I was drawn to the projects happening at INL.”

One of Ohene Opare’s favorite aspects of his job is that it cuts across disciplines to solve problems. Although his home organization is Energy & Environment Science & Technology, he’s able to contribute to various projects across the laboratory.

He said when he returned to the lab in 2017, he noticed a lot of improvement in inclusion, particularly in how the lab is working to make international employees feel more welcomed. Instead of having what he calls “the leprosy badge,” aka the red and white striped badge indicating a person was an international employee, now international employee badges have a much subtler blue color, versus the green color U.S. citizens’ badges display. Even something as simple as changing the way a badge looks can go miles for inclusion.

One thing Ohene Opare has carried with him from Ghana is his view on the importance of interpersonal relationships. “People in Ghana might not have much in material riches, but their wealth is in their relationships,” he said. Ghanaians value personal interactions and getting to connect with people.

“Sometimes we focus too much on things. We lose sight of the individuals behind it,” said Ohene Opare. He would like to see more people give others an opportunity. “Yes, I’m black. But I’m many things, just like how other people here at INL are many things. Let’s celebrate our laboratory’s multiculturalism and the backgrounds of people, beyond how people look, and get to know each other.”

When Ohene Opare thinks about “inclusion,” he thinks about it in terms of “interdependence.” “Everyone here has something to offer,” he said. “I depend on your skills, you depend on mine – and together we can make something magnificent.”

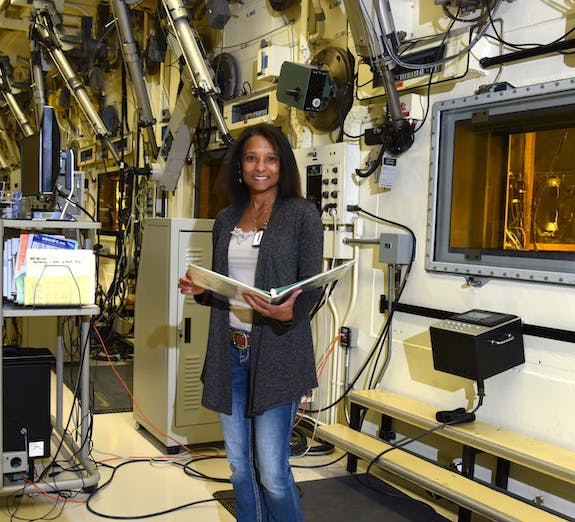

Meet Lynne Coe-Leavitt

Lynne Coe-Leavitt is the Health and Safety manager at the Materials and Fuels Complex (MFC), Transient Reactor Test (TREAT) Facility, Remote-handled Low-level Waste (RH-LLW) facility and select research laboratories at the Idaho Nuclear Technology and Engineering Center (INTEC). She’s worked in the health and safety area of the lab for over a decade, but started at INL in 1989 working at the Specific Manufacturing Capability as a laboratory technician. She holds bachelor’s and master’s degrees in safety engineering and is also a board certified industrial hygienist.

Coe-Leavitt said she likes the diverse array of R&D and assembly and testing operations she gets to work with at MFC. “My job is engaging and I’m always learning. The people I work with are pretty amazing.” She said even if she comes to work with a planned agenda for the day, most days those plans go out the window. “In my line of work, we have to be responsive and supportive to the customer’s needs. It comes with moments of stress, but it’s fun and interesting work.”

When Coe-Leavitt began college at Weber State University, she was intent on going to nursing school and becoming a surgical nurse. But at the time, it was not a high-demand field, so she switched majors and began studying manufacturing engineering. After two years of school, she got a job at Westinghouse. There, she met colleagues who were from Idaho Falls trying to hire on with INL. “They told me what a great place INL was to work and encouraged me to apply. I finally did and was hired a week later at SMC.”

The Idaho Falls area didn’t have the same engineering program, so Coe-Leavitt changed her studies to safety engineering. She said she never imagined living and working in Idaho, but she’s now happy to call Idaho her home.

Coe-Leavitt’s father was in the Air Force, something that allowed her to travel and experience the world when she was growing up. She was born in Amersfoort, Netherlands, but has lived all over the world – including Germany and locations throughout the U.S. Like many Americans, Coe-Leavitt has many cultures in her heritage – French Canadian, Cherokee Indian and African American. “Growing up in Germany on a military base was a diverse environment with kids of different nationalities, races and religions. No one seemed to notice or care that we were different.”

But in some areas of the world, differences were more apparent. For instance, when her dad was stationed in South Carolina, he and her mom didn’t go out in public together often because, although both are African American, her mom was very light-skinned and “it always caused problems with the police and others thinking my dad was with a white woman.”

While living abroad, when Coe-Leavitt and her three brothers would visit cousins in the states, they would tease them about acting and talking “white.” But she jokes, “that was just how we talked.”

“It seriously didn’t hit me that I was black until I moved to Utah,” Coe-Leavitt said. Her family moved to Utah in the 1970s, the last base where her dad was stationed before he retired. “A white kid at my new school came up and told me I was black. At that moment I thought, ‘Well I guess I am.’” She said she didn’t really understand why she and her siblings were treated differently than other kids, but they tried their best to fit in.

Coe-Leavitt said as she continued through middle and high school, some of her friends’ parents didn’t want their son or daughter to be friends with her or date her because of her race or religion. However, she doesn’t let her experience taint her view of all Utahans. “People are people – there are good people and bad people in any race or religion.”

Coe-Leavitt said her experiences growing up taught her lessons that she’s passing on to her daughter. “I believe prejudices can be tempered in the home environment. It’s our job as parents to teach our kids acceptance for those who are different. Treat others like you would want to be treated or like you would like your child or wife to be treated.”

Coe-Leavitt said she’s seen lots of positive changes toward a more inclusive environment in her time at INL. She said she’s happy to see efforts attracting employees with different education, cultural backgrounds, races and religions.

To Coe-Leavitt, it’s also important to share history with kids so they can understand how far we’ve come in gender and racial equality. “Black History Month is a remembrance of those who risked their lives for the betterment of the black community. It’s important for younger generations to understand the sacrifices endured to provide them with equal rights and a better life. It’s also important to never forget this part of history – it helped shape our nation.”

Meet Gabriel Ilevbare

Gabriel Ilevbare is a materials science and engineering department manager in INL’s Energy & Environment Science & Technology directorate. Prior to joining INL in 2016, he worked as a project manager at the Electric Power Research Institute in the Palo Alto, California, office. Here at INL, his job is to understand research methodologies and execute strategies to achieve the goals and objectives of the laboratory.

Ilevbare said he never imagined living in Idaho. “All we knew about Idaho was that’s where potatoes came from,” he said. “But everyone here has been wonderful – they are some of the most pleasant people I’ve ever worked with or lived amongst, and I’m very proud to be part of the INL family.”

There’s no magic ball to predict the direction of a person’s life, but Ilevbare said he thinks this is the right path for him. He grew up in Ibadan, Nigeria, and earned his bachelor’s degree in industrial chemistry from University of Ibadan. Ilevbare left Nigeria when he was 22 years old to earn his doctorate in materials science and metallurgy at University of Cambridge in England on a full-ride scholarship.

Some people may not know much about Nigeria, or Africa in general. Now a U.S. citizen, Ilevbare is very proud of his Nigerian heritage. “Many people in Nigeria where I grew up are well-educated, middle-class families. My father has a Ph.D., my mother is a business owner. I have two siblings who also have Ph.Ds. My wife, also from Nigeria, has multiple degrees.” He said the picture painted on the news or by politicians isn’t always accurate.

Ilevbare said often people think immigrants don’t have alternatives and end up in the U.S. because they don’t have other options. In reality, many immigrants like Ilevbare have lots of choices where to live their lives. “My family had a choice, and we chose to love this country,” he said of the U.S.

Making that choice has required sacrifices, however. When Ilevbare made the choice to leave his home country at such a young age, he knew it would result in the loss of certain things. Before he left, his father explained what he’d be giving up, “There will be no dad, no mom, no sisters, no brothers, no aunts. You can’t just travel to the next street, the next city. It will just be you. Thousands of miles away.”

At the time, Ilebvare just shrugged his shoulders and said, “OK.” In reflecting on it now, he’s not sure whether he would have made that decision so casually, but said it has worked out, and he is happy with his life and his decision to make the U.S. his home.

One thing he’s experienced that other native-Idahoans might not encounter is a feeling that he must justify his existence in his job – to prove he deserves to be where he is. “There’s a general perception that those who are minorities got a pass, that we got a bye and didn’t earn it.”

The great thing about INL is that the laboratory is building world-class capabilities and investing in the right people to build a world-leading team. “We have an opportunity to go out and hire the best people we can. We can invite them to be part of this family in Idaho.”