Camp Buehring, a United States military base nestled in northern Kuwait just 20 miles from the Iraqi border, faces a challenge: there are no wells, rivers or other easily accessible sources of water.

In this arid region, water is a precious commodity. Soldiers rely on trucks to deliver the water they need for showers, drinking and flushing toilets. With an average annual rainfall of less than six inches and temperatures ranging from 70-80 degrees Fahrenheit in winter to a scorching 108-115 degrees in summer, managing water resources is crucial for their survival.

“They have to bring in all their water,” said Jeremiah Gilbert, a distributed energy power systems engineer at the Idaho National Laboratory (INL). “It can get really expensive, so we wanted to look at ways they could recycle water. Our goal was to create water resiliency for the troops and support the military’s mission to have their bases be more self-sufficient.”

Gilbert and his fellow researchers received funding from the Department of Defense (DOD) to perform an energy assessment of two military bases in the area.

“We went through the bases looking for ways they could improve or reduce their energy use,” said Mike Shurtliff, the project manager and a systems research engineer. “We wrote several proposals on how they could save energy and money.”

One of the accepted proposals was to install a water reclamation system (WRS). These systems recycle water, reducing the number of water truck trips.

Shurtliff said Army regulations require that all water provided for consumption and use must come from a controlled source. Water in Kuwait is largely provided by in-country desalination plants. The water from those plants is tested on-site to ensure it meets Army standards.

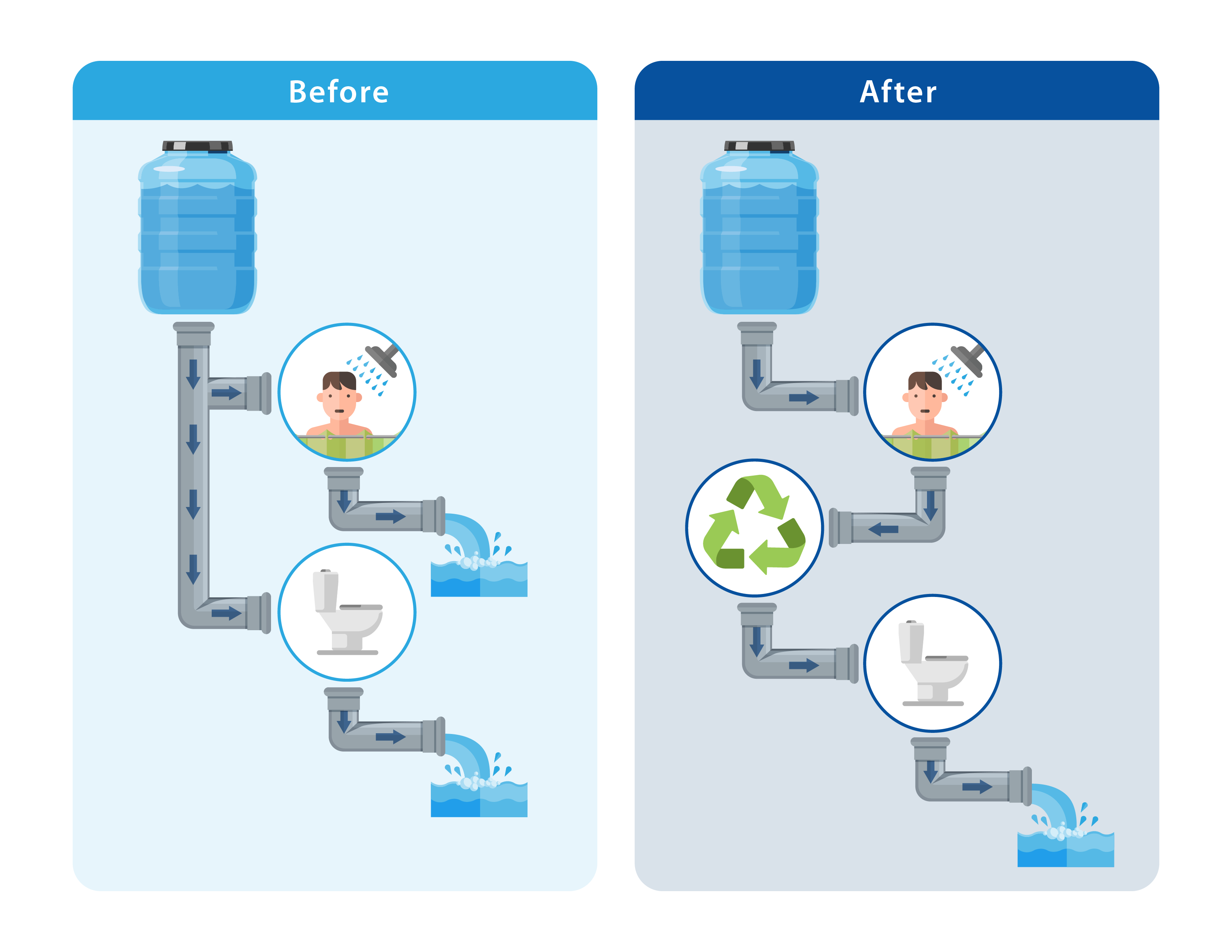

“One of the ways to improve their resilience, based on what we saw at the bases, was to reuse water,” said Shurtliff. “Our proposal was to design a water reclamation system that would take water from showers and sinks, clean it and reuse it to flush toilets.”

Water used at Camp Buehring goes down the drain and is effectively lost. The WRS eliminates single usage, increasing the base’s water availability. DOD funded the proposal to cut costs and increase the base’s resiliency. The team looked at existing filtration systems and reached out to Greyter, a company that specializes in that area.

“Greyter has done a lot of water reclamation systems for housing and apartments,” said Shurtliff. “Their units are designed to filter and clean gray water. It’s not considered potable (consumable), but the reclaimed water can be used for toilets or laundry. We contacted Greyter and were able to purchase their base system. We worked with Diversified Inc., a local Idaho Falls company, to custom-build a transportable storage container to house the water reclamation system so that it could be delivered, easily connected and ready to operate.”

Gray water comes from sinks, showers, washing machines and similar sources. It generally contains chemicals like soaps and detergents. For the water reclamation process to be as simple and effective as possible, black and gray water can’t mix. Black water, which contains human waste and harmful bacteria and pathogens, requires a more substantial cleansing process.

While the INL engineers designed a workable reclamation system, getting the system to Kuwait and installing it there posed challenges.

“The water reclamation system arrived at Camp Buehring right around when COVID hit,” said Shurtliff. “With the travel bans, we couldn’t go visit for about a year and a half. During shipping, the chlorine tablet containers were unsealed and exposed everything in the shipping container to chlorine. By the time we got to the camp and opened the container, most of the metal, including circuit boards and surfaces, was corroded.”

The team cleaned and repaired the WRS on-site and hooked it up to the shower and toilet units. However, soon after the WRS was set up, the contractor who provided the original toilet units withdrew their services and removed the units. The team quickly adapted by working with Army administration to connect the system to two other toilet units provided by a different contractor.

The camp’s water supply is delivered by truck and pumped into a holding tank and used for showers and hand washing. When it drains away, the water is sent to a gray collection tank. From there, it’s pumped to the WRS where it undergoes filtration, is mixed with chlorine and then put in a tank for storage. Before it reaches the toilets, the water is run through ultraviolet exposure as an additional precaution to ensure the water is safe for human contact. Then the water can be used for toilets, watering plants, dust control and other non-potable uses. All water flushed down a toilet is sent through the sewer system to a man-made lagoon off base for treatment.

“The WRS has been successful,” Gilbert said. “There’s interest from the military in adding another layer of cleaning to create drinkable water.”

After managing it for a year, INL handed the WRS off to the Army to maintain. The project was just one example of how INL innovates and implements solutions for military installations to support DOD’s resilience and self-sufficiency goals around the world.

“Our hope is that we can use the success of this demonstration project to develop several more,” said Shurtliff.