There’s no way of knowing for sure, but there was probably no more reluctant a war hero than Sgt. David Bleak. A Medal of Honor recipient for heroism in the Korean War – his story of courage under fire is an incredible one – Bleak was much happier talking about farming, Western novels or his grandchildren, say the people who knew him best.

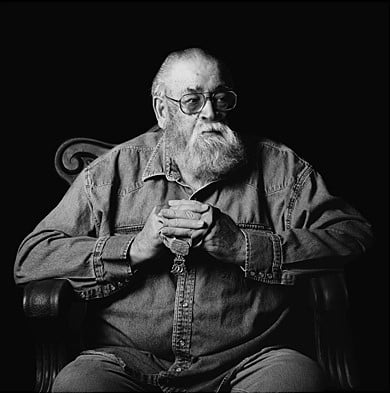

A longtime employee at Argonne National Laboratory-West, now Idaho National Laboratory’s Materials & Fuels Complex, Bleak, who died in 2006, is remembered as a “gentle giant.” He was 6-foot-4-inches with a huge neck and giant hands. “Boy was he big,” says Emil Berry, who was a member of the manipulator control group and frequently encountered him on the job. “I used to call him the book reader, because he always had a Louis L’Amour paperback with him.”

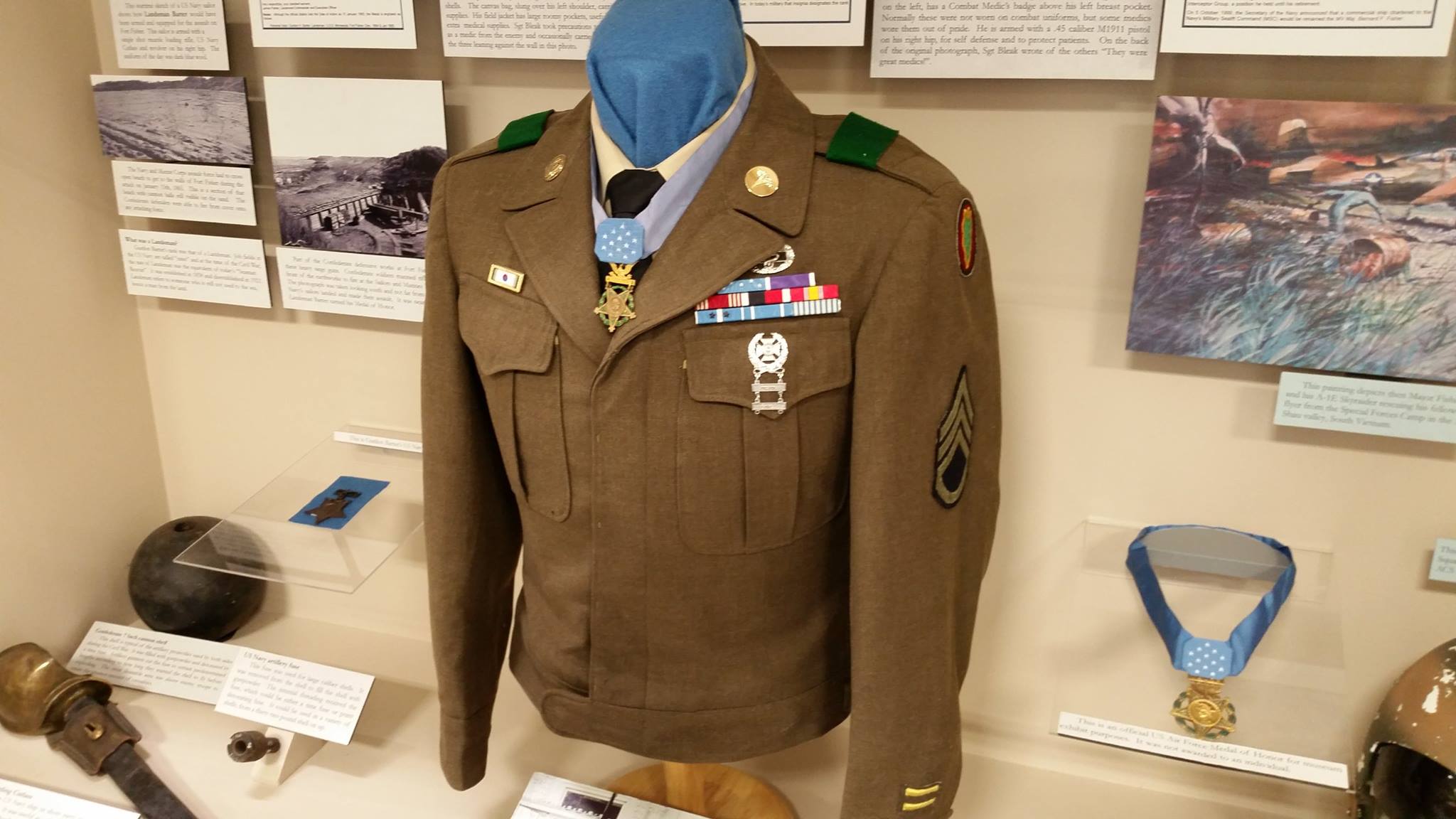

It’s impossible to write about Bleak without recounting his actions on June 14, 1952, when he, an Army medic, accompanied a patrol behind enemy lines to capture an enemy soldier for interrogation. In an article published last year in the Lewiston Tribune, Bleak’s gripping story accounted how he stormed an enemy trench with only his trench knife to defend his fellow soldiers from attack. Returning to his patrol, he shielded a soldier from a concussion grenade after it had bounced off his helmet. With a bullet in his left calf, he was carrying a wounded soldier downhill when he encountered two enemy soldiers. Bleak dropped his comrade to overtake the enemy forces, then resumed carrying the wounded soldier back to safety. He was ready to go back into the fray when a commanding officer told him he was done for the day.

What might have been going through his head at the time, besides pure adrenaline, no one will ever know, because he talked about it rarely, if ever, family members say. His efforts ultimately led to all 20 of his fellow soldiers returning alive.

“He had to get those people out of there safely,” said his widow, Lois Bleak of Arco. “He couldn’t understand why everybody wanted to make such a fuss over him. He was just doing what everybody else was. The difference was he was twice as strong.”

Unlike Sergeant York in World War I, Hollywood never made a movie about Bleak. There was no parade, but he was honored in a ceremony at the White House in October 1953. There President Dwight Eisenhower bestowed the Medal of Honor on Bleak, and was reported to have whispered, “You’ve got a big neck!”

With the formalities over, Bleak went back to his job as a truck driver and meat cutter for a grocery store in Dubois, Wyoming, which is where he met Lois. The couple moved to Shelley, and eventually he landed a janitorial job at Argonne-West. He remained at the facility, advancing in his career until he retired in the mid-1990s as a chief hot cell technician.

“He was a humble guy,” Berry said. “For the longest time I didn’t know he’d received the Medal of Honor. He was just a guy who monitored the cell in HFEF (Hot Fuel Examination Facility) North.”

Gene Winter, another former Argonne colleague, remembers an unassuming co-worker who smoked cigars in the hall (“In those days, you could”) and didn’t say much. “I didn’t know him that well, but he always struck me as one of those crusty old guys you’d better not mess with.” His size and strength were somewhat legendary, and there was a story about a lead brick falling on him once. “It would have laid anyone else out, but we heard he went down to one knee, then got back up and went back to what he was doing,” Winter said.

“He never said much about his Medal of Honor, but people at work knew about it,” Winter said. “When I heard he’d been awarded the Medal of Honor my whole view changed, but he never made a big deal about it. He was just a guy.”

Bleak’s diligence and commitment to duty earned him a promotion to engineering technician at the Hot Fuel Examination Facility. “Argonne supported its people, and if you were military, they were really behind you,” Berry said. Today, a road leading to the Materials and Fuels Complex bears Bleak’s name as tribute to his military and national laboratory service.

Bleak’s diligence and commitment to duty earned him a promotion to engineering technician at the Hot Fuel Examination Facility. “Argonne supported its people, and if you were military, they were really behind you,” Berry said. Today, a road leading to the Materials and Fuels Complex bears Bleak’s name as tribute to his military and national laboratory service.

Medal of Honor recipients are entitled to special perks, including a monthly pension, special recognition ceremonies and invitations to presidential inaugurations. Winter remembers Bleak received one such invitation. His boss, a by-the-book former Naval officer told him he would not be able to go because he was working on an important project, but Argonne upper management was notified by the White House that Bleak would have time off to attend the ball as a guest.

“He enjoyed working at the Site,” said Lois Bleak. “He was doing things he loved to do. He was very good at fixing things, building things, and trying things out.” He was also able to learn new skills and advance in his career. “They let him go ahead and study what he needed to get ahead,” she said. “We were just so proud of him, and he was having a great time doing the things he liked.”

“Kids would say, ‘Your dad’s a war hero,’ but he was my hero because he was my dad,” said his son, Bruce Bleak, 62, of Arco. “He was just always there.”

In all the time he knew his father, Bruce Bleak said he never heard him talk about his combat experience. He would talk about things that happened while in camp, such as the time they got hot water for showers by persuading the Army Corps of Engineers to weld beer cans together to make them a pipeline. “It sounded like quite a genius project,” he said.

But combat? Never a word. Still, there were times he saw a faraway look on his father’s face, what’s commonly known as the thousand-yard stare. “The combat, it never really leaves them,” he said. “But I never heard anything from him about his time in battle.”

The family farmed near Moore, north of Arco, raising sheep and cattle and growing hay and grain on 80 acres irrigated by the Lost River. “It was a lot of work, but he loved farming,” Lois Bleak said. “But the job at the Site paid better, and he loved doing that, too.”

Together, they had four children, and at the time of his death, David and Lois Bleak had nine grandchildren and six great-grandchildren. Eighteen years after his death, Lois Bleak remembers a gentle man who loved farming and children. “He could charm a baby or a little kid,” she said. “He was really great with children.”

Medal of Honor recipients can wear their uniforms any time or anywhere they choose and wherever they go active-duty service members are obligated to salute them. When they die, they may receive burial with full military honors in Arlington National Cemetery. Sgt. David Bleak chose to be cremated and have his ashes spread on the land he loved. His Medal of Honor was donated to the Idaho Military History Museum in Boise, where it is displayed with an account of his heroism.