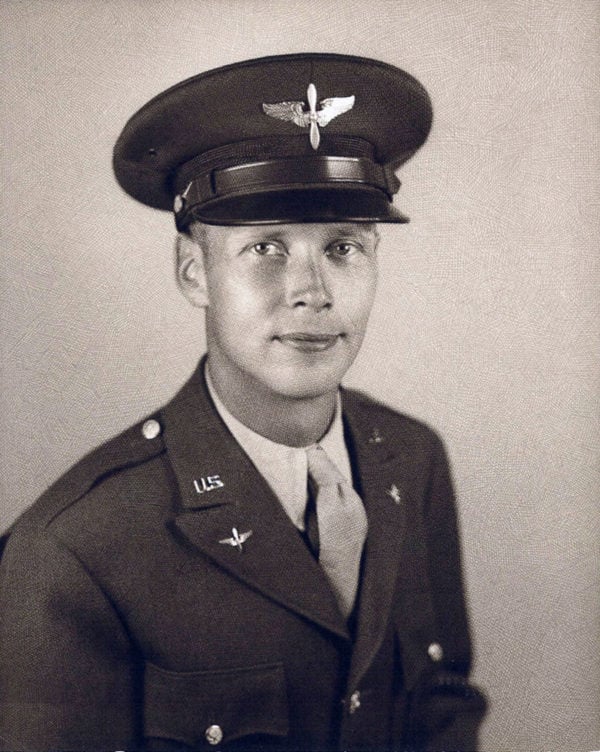

In late June, Roberta Armstrong came as close as she would ever get to her father, Lt. Robert W. Madsen, a U.S. Army Air Corps member who died in a World War II training accident on the Idaho desert. Armstong’s mother didn’t even know she was pregnant in January 1944 when she learned her husband had been killed when B-24J 42-73365, a four-engine “Liberator” bomber, crashed near the Middle Butte while training on the Arco High Altitude Bombing Range.

“I never knew my dad. He was kind of this mythical figure in my life,” said Armstrong, who came to Idaho in late June to attend a ceremony honoring the B-24J bomber crew and their sacrifice 80 years ago. The day before the June 29 ceremony she and her husband, Al, visited the crash site, which was only discovered in 2014 after lying undisturbed for close to 70 years. Today at the site, a small granite marker honors the men who died: Lt. Richard A. Hedges, Lt. Lonnie L. Keepers, Lt. Robert W. Madsen, Lt. Richard R. Pitzner, Sgt. Louis H. Rinke, Sgt. Charles W. Eddy, and Sgt. George H. Pearce, Jr.

Armstrong came with the scrapbooks her mother had kept of Lt. Madsen’s time in the Air Force. Most of his training was in San Antonio, Texas, at what is now Lackland Air Force Base. His posting at the Pocatello Army Air Base was only supposed to last three to four weeks. Crews would drill by flying out to the Arco range and dropping dummy bombs filled with sand (many of which are still on the ground, covered in rust.) As the plane’s navigator, Madsen, one of the four officers on the plane, guided the pilot where to go except during the actual bombing run, when it was the bombardier’s job to use the Norden bomb sight, fly the aircraft, and release the bombs.

According to the U.S. Army Air Force’s accident report, the plane left the airfield at Pocatello at 8:05 p.m. Most of the crew had returned from Christmas furlough and were due to ship out soon. The war was far from over. D-Day was only four months away, and the campaign in the Pacific was slowly moving northward island to island.

Going by the flight log, which is included in Armstrong’s second scrapbook, Madsen had less than 90 minutes of time in the air out of Pocatello before the plane crashed. The tower operator at the bombing range reported seeing the plane at 8:50 p.m., and at 9:05 p.m., after it had made three passes at 20,000 feet. Sheepherders on the base of the butte that night had an even closer view. They recounted to investigators how they saw the plane flying low over the desert trying to regain altitude before going into a spin at 500 feet, then crashing into the ground and exploding. It took five minutes on horseback to get to the scene. They searched for survivors but were hampered by the heat of the explosion and subsequent fire.

Crews from the Army Air Corps recovered the major parts of the wreckage, but much debris remained on the ground. When the land became part of the Atomic Energy Commission’s National Reactor Testing Station in 1949 it became off limits to the public. If not for the efforts of Marc McDonald, a Pocatello historian aircraft enthusiast and volunteer with Project Remembrance, memory of this tragic event may have been lost to time. After poring over Air Force registry records, McDonald called INL’s Cultural Resources team in January 2014 to tell them he believed there was a crash site on the desert.

Using old photos, GPS and satellite images, they identified three possible crash site locations. In March 2014 they set out on foot. After the first two searches yielded nothing, the group found an aluminum gauge in the brush at the third location. Spreading out, they found more debris — engine sections that had broken up, wires, coils, solenoids, .50-caliber shell casings, even an electric socket plate from the front of a flight suit (B-24 cabins were not pressurized or heated, so crewmen wore clothing that plugged in like an electric blanket.)

Armstrong got a call in 2014 after the site had been discovered, but there were no plans on INL’s end for inviting family members to visit the crash site. The first family member to visit, in 2016, was Nancy Gavalis, daughter of Sgt. George H. Pearce, Jr. During their initial search, INL archaeologists had found a woman’s 1935 high school class ring with WHHHS on its stone and the initials M.A.H. inside. Records showed Pearce had been married to Madeline A. Hopkins and that both had graduated from William H. Hall High School in West Hartford, Connecticut. From there, INL’s team tracked Gavalis down at her home in New Hampshire and told her they’d found the ring that had been hanging around her father’s neck at the time of the crash. Like Armstrong, Gavalis, who was 2 in January 1944, had no memory of her father.

Armstrong was the only family member of the original seven airmen able to attend the 2024 ceremony, which included a three-volley salute by Veterans of Foreign Wars Post 2146, presentation and retirement of colors by the United States Air Force Auxiliary, Civil Air Patrol, Eagle Rock Composite Squadron RMR-ID-097, and remarks from McDonald, DOE-Idaho Manager Lance Lacroix, and Nicholas Holmer and Reese Cook of INL Cultural Resource Management Office.

The U.S. military’s documentation and cleanup of crash sites wasn’t comprehensive until the 1990s, McDonald said. Civilians have been trying to relocate lost crash sites since the 1960s. Project Remembrance started about 20 years ago to unite civilians who had been looking for wrecked aircraft on their own for decades, he said.

A little-known fact that has finally emerged is that between 1942 and 1945 roughly 15,000 airmen lost their lives in stateside training accidents. Because of wartime secrecy, families weren’t given many details about what happened when a flier was killed in training. It was the U.S. Army Air Force’s policy not to bestow decorations on those not killed in combat. For the victims of training accidents, “There was no honor or recognition,” McDonald said.

Following the January 1944 crash in Idaho, Armstrong’s mother sought to join the Army Air Forces herself. That ended when she was told she was pregnant. She eventually remarried, and Roberta grew up in Minnesota. She grew up to earn a doctorate in psychology and now lives in New Mexico.

“I’ve had a great life, but I still do wonder from time to time how it would have been if my dad hadn’t died,” she said.