Harold McFarlane’s mostly empty office, in the northwest corner on the third floor of Idaho National Laboratory’s Engineering Research Office Building (EROB), offers a clear view of progress.

In barren fields where moose and deer once roamed now sits a busy University Boulevard, with its Center for Advanced Energy Studies and Energy Innovation Laboratory, homeland security buildings and INL Meeting Center.

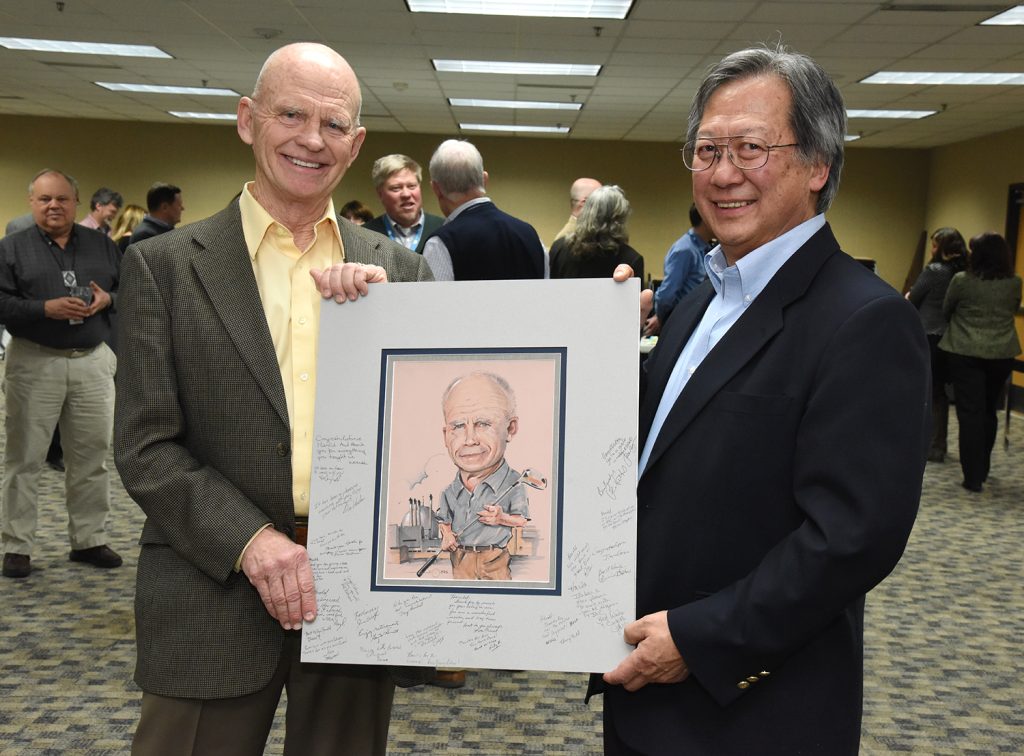

All these facilities, programs and new hires resulted from generations of INL employees who did their jobs well. Expansion follows success. And few have done their job better or known more success than McFarlane, who is retiring next month after four decades at INL.

“If you are going to try to pay tribute to Harold McFarlane, you are going to need lots of time and lots of paper,” Idaho Rep. Mike Simpson wrote into the Congressional Record. “Harold’s accomplishments and contributions as a scientist, an administrator and a leader are as impactful as they are extensive.”

A native of the border town Del Rio, Texas, McFarlane never wanted to be anything but a scientist. He earned a Bachelor of Science degree from University of Texas, and a Ph.D. in engineering science from the California Institute of Technology, where he also taught.

“Those were some of the most brilliant students you could have,” McFarlane said. “So, it kind of spoiled me.”

From there, McFarlane traveled to New York University, and what appeared to be a bright future in the Big Apple. McFarlane was selected to run a nuclear energy program and nuclear reactor the university planned to import.

The struggling American economy intervened. A $5 million program was slashed to $50,000. The reactor never showed up. McFarlane headed west.

A career in Idaho

He and his wife, Mary Ellen, arrived in Idaho Falls in August 1972. Newly hired by Argonne National Laboratory-West to work at the Zero Power Plutonium Reactor (ZPPR), McFarlane didn’t imagine sticking around for the long haul.

“I thought it was kind of an old business when I got in,” he said. “I didn’t expect to stay in more than one or two years.”

McFarlane hit the ground running, developing first-of-its-kind measurement and data application techniques. He later took charge of the ZPPR Critical Experiment program, which supported the design, safety and licensing of fast spectrum reactors large and small.

In the early 1990s, McFarlane became Argonne-West’s site director, then assistant lab director for nuclear oversight.

From 1993 on, his focus shifted to fuel cycle technology and helping transfer the radioisotope power system mission from Mound, Ohio, to Idaho.

Following the birth of Idaho National Laboratory in 2005, McFarlane took on two roles: deputy associate laboratory director for nuclear programs; and director of the lab’s Space Nuclear Systems and Technology division, which helped power NASA’s one-way trip to Pluto aboard the New Horizons spacecraft.

It came as no surprise when, following Fukushima, the Department of Energy brought McFarlane to Washington, D.C., to advise Energy Secretary Steven Chu about what was taking place on the ground.

“Harold has the very rare ability to work seamlessly across the technical, policy and diplomatic worlds,” said John Kotek, acting assistant secretary for the Office of Nuclear Energy. “He also has a knack for zeroing in quickly on the truly important issues, and can persistently and creatively work those issues through to resolution. He’ll truly be missed by me and my DOE colleagues.”

McFarlane’s involvement with the American Nuclear Society (ANS) began before he stepped foot in Idaho. In 1970, he attended a meeting in California and served as an adviser to the ANS student section while at NYU.

As McFarlane’s career progressed, his involvement in the organization continued to evolve. He chaired ANS’ Reactor Physics Division, and the Fuel Cycle and Waste Management Division. In 2006, McFarlane became the 52nd president of ANS, a task he approached with his usual expertise and energy. One area of emphasis: telling the story, something McFarlane, an accomplished writer, considers an important part of the job.

“Dr. McFarlane promoted ANS’ value as the premier professional society for nuclear science and technology through continued knowledge development and transfer,” said ANS President Eugene Grecheck. “In addition, the Nuclear Advocacy Network was initiated under his leadership, which has engaged nuclear professionals more directly in public policy discussions over the past 10 years.”

Replacing this generation

A very real question for INL, and the nuclear energy industry, is where the next generation of Harold McFarlanes will come from.

Thirty percent of INL’s workforce is at least 50 years of age and, like McFarlane, at that point where they are either retiring or thinking about it.

For INL, and its mission of advancing nuclear energy, securing and modernizing critical infrastructure, and enabling clean energy deployment, educating, training, recruiting and retaining the next generation of researchers, engineers and support staff are vital.

“We understand how difficult it will be to replace Harold, and many other key employees nearing retirement,” INL Director Mark Peters said. “But we have no choice. Helping provide the clean energy needed to power our future and secure this nation’s critical infrastructure depends on our ability to replace folks like Harold. That means the lab must continue to support STEM education, accessible higher education whose curriculum aligns with industry needs, and on-the-job training through internships and joint university appointments.”

The coming “silver tsunami” of baby boomer retirements alarms industry leaders, and those who understand the importance of places such as INL to their state and regional economies.

INL is Idaho’s fifth-largest private employer. The lab spent $130 million with Idaho businesses in 2015 and contributed more than $682,000 in charitable giving to the community.

As Peters said, the lab’s ability to fulfill its mission – and contribute to the economic well-being of the state and region – depends on replacing folks such as McFarlane.

The upside of this, of course, is that INL’s growing business volume and coming wave of retirements foreshadow opportunity for those students who, like McFarlane in his native Del Rio, Texas, dared to dream big and build a STEM-education foundation upon which to create a long and fulfilling career.

“It’s our hope that Harold’s distinguished career will serve as an inspiration to the next generation,” Peters said.

That foundation can launch students in many different directions. McFarlane is proof of that. From Texas to California to New York to Idaho to Washington, D.C., he’s seen much and accomplished more.

His message to students? Never stop learning. McFarlane didn’t. In 2000, at the age of 55, he graduated with honors from a Master of Business Administration program at the University of Chicago. Expect change, McFarlane says. Prepare yourself to deal with what comes.

“You just can’t count on things always working the way they seem today,” McFarlane said.

Resiliency is also important. McFarlane’s 44-year career at INL has earned him many awards and accolades. But there have been bumps in the road: programs discontinued, budgets zeroed out and projects shut down. And yet, McFarlane persevered and has the distinct pleasure of walking away knowing that he – and many others – left their profession better than they found it.

What’s next?

Harold and Mary Ellen McFarlane share a passion for chasing a little white ball around large and well-fertilized fields of green.

Mary Ellen, who comes from a family well-known in Texas golfing circles, has won a string of club championships and once teamed with Harold to claim an Idaho State Couples Championship.

It makes sense that this analytical man finds pleasure in the game that can’t be mastered, never stops providing lessons and rewards those who practice and prepare.

In the ancient and royal game, optimism and pessimism have nothing to do with the work at hand. Hyperbole is no help. Not when your ball sits exactly 196 yards from a small sliver of green, surrounded by pond and sand, and the wind is blowing left to right at 16 miles per hour.

At that moment, you’d better possess clarity of mind, body and soul. If you don’t, well then, pull the pitching wedge and lay up.

There’s Mac reaching for his 5-iron.

So yes, look for Harold on the fairways and greens of the Idaho Falls Country Club, skiing at Targhee, snowshoeing in the hills south of town or pulling fish out of a nearby lake or river.

And who knows, you might just find him in front of a classroom or helping build a program intended to train the next generation. Colleagues across the country have been in contact. The scientist/teacher is curious to see if they’ve done their homework, if there is action behind those words.

“We’ll wait and see if they really mean it,” McFarlane said.

Wait and see. For the first time since Del Rio, Texas, Mac is free to do just that. And, really, isn’t that what retirement is about?