It might be tempting to think of cowboys and cattle drives, but the real story of the American West can be summed up in one word: water.

Since the 1870s, water and irrigation in the West have been source material for countless books and movies like “Chinatown” and “The Big Valley,” but today’s realities are leading to new ways of thinking. Irrigation infrastructure has exceeded its design life by decades and needs massive reinvestment.

While the costs might be daunting, the U.S. Department of Energy’s Water Power Technologies Office (WPTO) has teamed up with the Oregon-based Farmers Conservation Alliance to radically reimagine the role of irrigation systems in the West. The effort seeks to transform a critical piece of agricultural infrastructure into a system that encompasses energy conservation and renewable power generation, broadband communications, and wildlife habitat conservation.

Building off of the FCA’s Irrigation Modernization Program, two of DOE’s national labs – Idaho National Laboratory and Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) – are developing a decision-making tool that uses historic data and geographic information systems (GIS) to help inform key decisions about modernization. Together, the national labs are working to produce a case study that uses real world data to demonstrate the visualization tool’s functionality.

“After we prove the usefulness of the tool, the plan is to develop it into an open source public tool,” said Thomas Mosier, INL’s Energy Systems group lead. “The hope is to accelerate reinvestment in these systems to benefit farmers, local communities and the environment. There used to be this one-size-fits-all modernization model. The approach we’re seeing today is much more nuanced.”

History of irrigation in the West

Beginning in the late 19th century, a sprawling network of dams and canals transformed roughly 40 million acres of sage-covered desert in 17 Western states into arable cropland. After passage of the 1902 Reclamation Act, Congress appropriated millions of dollars over decades for large-scale irrigation development. Projects such as Hoover Dam on the Colorado River and the Grand Coulee Dam on the Columbia were hailed as modern wonders of the world, but the West is dotted with smaller dams and reservoirs.

The era of big reclamation projects ended in the 1970s, with concerns emerging about fish and wildlife habitat, and other energy sources moving to the forefront. As the world has moved on to face new sustainability challenges, existing irrigation systems, inland waterways, levees and dams have remained for the most part frozen in time, the newest of them now nearly a half-century old.

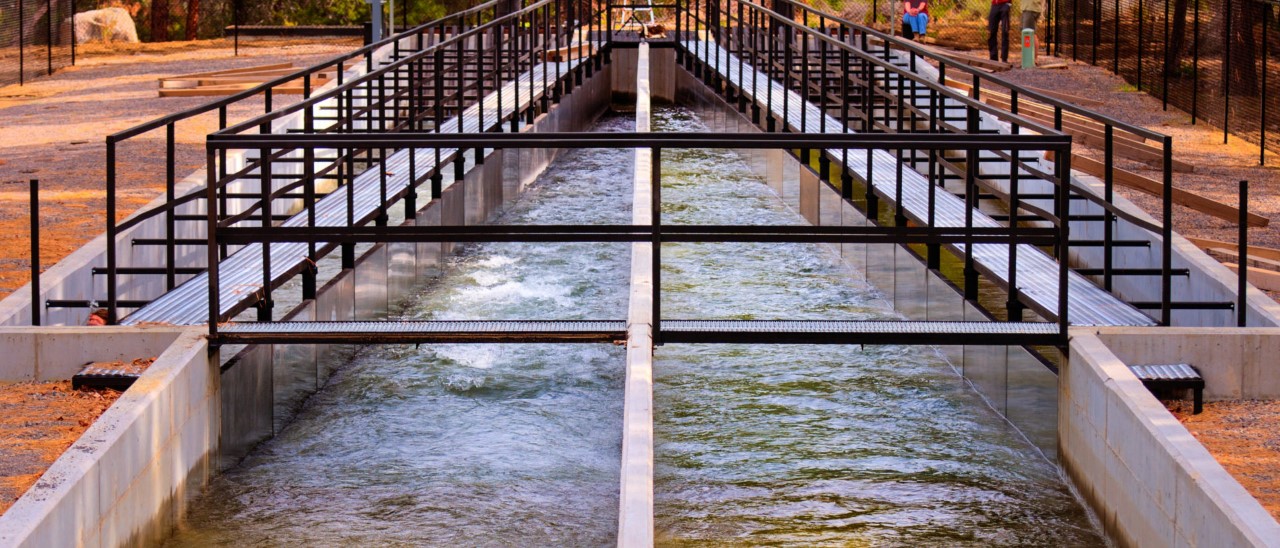

Technology has advanced, however, and pressurized pipe has been developed to deliver water more efficiently. In traditional canals, anywhere from 45 to 85% of water can be lost to seepage and evaporation. Pressurized pipe has made it possible to deliver water without loss while generating hydroelectricity, also reducing the amount of energy needed for pumping. Since most pumps are powered by diesel fuel, this represents a reduction in carbon emissions as well.

Modeling modernization trade-offs

Modernizing the country’s irrigation systems can enable higher value crops and protect farmers in times of drought. Yet those benefits are a mere drop in the bucket. Irrigation modernization also offers possibilities for enhancing streams and aquifers, reducing chemical usage, bolstering rural power resilience, and bringing good jobs for rural communities.

Stakeholder engagement is essential, and with support from WPTO, INL and PNNL are working with farmers, canal companies, irrigation districts, manufacturers, municipalities, utilities, governments and nongovernment organizations.

The team’s immediate objective is to develop a visualization tool that assesses trade-offs in modernizing irrigation design and enables diverse stakeholders to have conversations about modernization options, Mosier said.

A simple discussion might involve weighing the possible economic benefits of converting 5 miles of open canal to pressurized pipeline. Controlling water flow through the pipeline creates hydroelectric power that can be sold, but is it enough to make up for the conversion cost of approximately $1 million per mile? The decision support model will analyze the cost burden in relation to the money that would be generated by power sales.

Beyond that, however, there are other factors. While many would consider seepage from an open canal to be a bad thing, an irrigation district that relies on a spring downstream would consider aquifer recharge from the seepage to be essential to them getting the water they’re entitled to. Such issues as these have made water rights in the West very contentious at times.

“We’re building an analytics engine that will allow different conclusions with different variable inputs,” said Shiloh Elliott, an INL modeling and simulation scientist. For any such engine to work, it must be quantified with academic rigor, using known physics and geoprocessing tools, she said.

While INL addresses the data aspects, experts at PNNL are building a computer interface “dashboard” that will let users visualize the trade-offs and compare options.

Gathering data is one of the main challenges, said Bo Saulsbury, senior project manager at PNNL. At one end of the irrigation world there are operations like California’s Imperial Irrigation District, which has sensors and extensive datasets. At the other end are smaller rural districts gathering data much the same way they have for decades. Irrigators can volunteer to share their data, which will improve the dashboard.

Collecting whatever data they can find from the widest number of sources, INL and PNNL plan to have an initial demonstration ready for WPTO this summer. The data will be synthesized from various sources but representative of what one might see from a typical irrigation district, Saulsbury said.

As time goes by, the team members said they hopes water users will see the opportunities that the analytics engine can identify and will participate by entering their own data. The expanded pool of water user data will improve the decision support model being developed at INL by Mosier, Elliott and colleague John Koudelka.

Help for agricultural communities

In some Western states, irrigated agriculture constitutes more than 90% of total water use. It remains a dominant economic driver, especially in smaller rural communities. But as critical as agriculture is to the economy of the region, farmers, canal companies and irrigation districts find themselves in a limited position to modernize infrastructure on their own.

“One of the challenges is that irrigation infrastructure is expensive, and agriculture is typically a low-margin undertaking,” Mosier said. That’s why a modernization effort will require collaboration among a diverse range of experts.

“The margins in agriculture are so small that the districts need help,” said Margi Hoffmann, FCA’s strategic operations director. “Modernizing these systems not only reduces operations and maintenance costs, it can create increased flow or enhanced water quality that benefits the river system as a whole. Modernizing irrigation districts is one of the greatest opportunities to benefit food, farms and fish.”

FCA teamed up with DOE three years ago, providing the national labs with the foundation for their work in irrigation modernization today. “The national labs have a breadth and depth of expertise and an understanding of the technology we need to accelerate the pace and scale of the work,” Hoffmann said.

Water districts of the future

Roughly 80% of the water in 18 Western states is used for irrigation. With snowpack on the decline and glaciers shrinking in size, “It’s challenging not just for agriculture but for manufacturers, municipalities and wildlife,” Hoffmann said.

In fact, in the “Irrigation District of the Future” envisioned by the FCA, there is a broad and diverse group of stakeholders who benefit from modernization. It is a challenge to balance diverse interests, but Hoffmann said the projects they have undertaken in central Oregon in the past five years have given them cause for optimism. FCA’s website cites:

- 579 miles of modernized canals

- 38 megawatts of new renewable energy generation

- 59,650 mwh/year energy conserved

- Water conservation amounting to 557 cubic feet per second

- 111,833 acres of agricultural land protected

Better water management means farmers can continue to receive allotments they have been entitled to under laws dating back to the 1870s. Rural counties stand to benefit not only from increased agricultural production but from resilient energy systems, with water routed through pipes generating hydropower. The pipes also offer conduits for fiber-optic cable, bringing broadband capability and a stronger foundation for economic development.

Environmental interests can look to safe passage for migratory fish at irrigation and hydropower diversions, reduced carbon emissions from fewer diesel-powered pumping stations, and increased streamflow and better water quality in rivers.

Once a modernized irrigation and renewable energy infrastructure is in place, numerous benefits could follow for rural communities. These include electric vehicle (EV) charging in remote locations, city or county EV fleet vehicles using self-generated energy, broadband access to rural areas, even remote seismic sensors.

Hydropower generation and fiber-optic transmission line leases represent a potential source of earned revenue, which could be used to match state and federal funds or meet annual loan payments, Hoffmann said. For local and state government, there will be new opportunities to implement statewide goals and visons in ways that meet local needs.

Partners throughout the West

FCA’s collaboration with INL and PNNL focuses on educating stakeholders. This includes irrigation districts and canal companies; federal, state and local officials; and utilities, both publicly and privately owned. While the organization has been focused on Oregon – leveraging $150 million in investment in the central part of the state over the past five years – it is also working with water districts in California, Montana and Nevada, Hoffmann said. Any district in 18 Western states is invited to reach out, she added.

“When we get in and look at the data, it shows the broad community benefits that modernization can provide,” Hoffmann said. This helps build the strategic partnerships necessary to drive investment districts needed to move forward.

Using the best data available, the project seeks to quantify trade-offs, articulate benefits and bring necessary stakeholders to the table, Mosier said. “It really depends on having a few local champions. From there, we can create a larger team of champions.”

UPDATE: The IrrigationViz tool was released in the summer of 2021. Read more here.