Postcontact History

Cultural Resources at INL

Fur trappers and early exploration

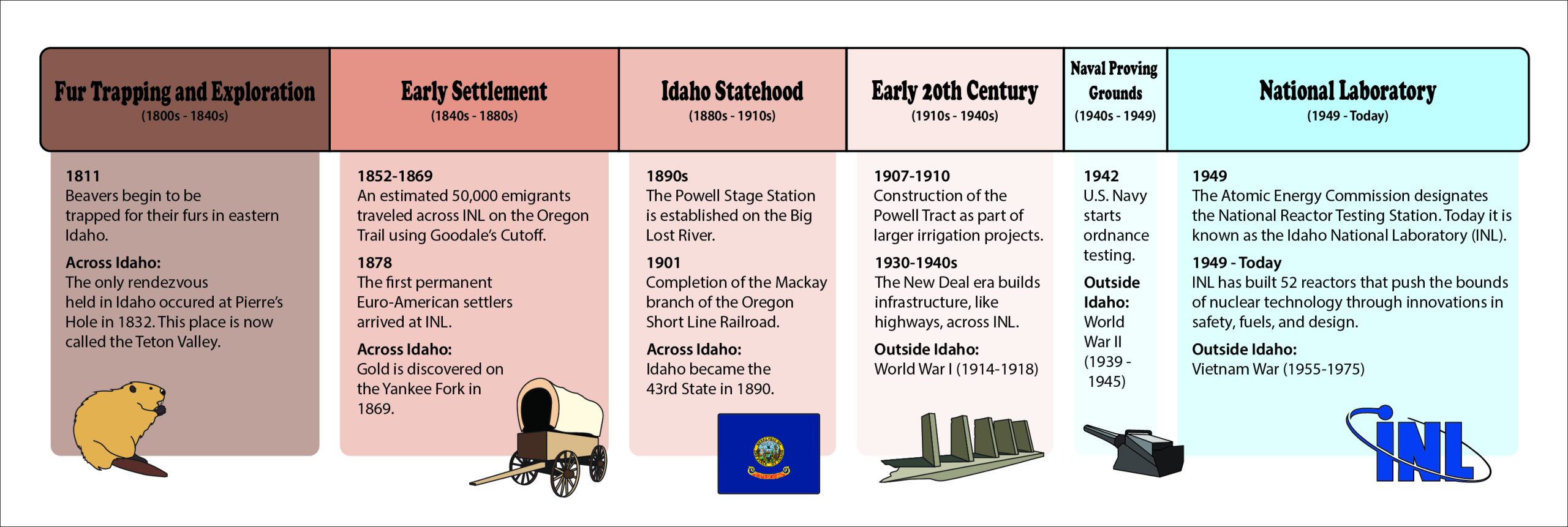

The fur trade marks the first time Euro-Americans went west of the Rocky Mountains for business ventures, starting an age of exploration and Euro-American Imperialism in the region. From 1811 to 1856, trappers traversed the Snake River country in search of beaver. During this period, Great Britain and the United States contested the Eastern Snake River Plain as both nations established a permanent presence and slowly eroded Native American holdings. The Hudson Bay Company controlled most of the trade on the Snake River Plain during this period and faced only some competition from American trappers. Most American business ventures in the area failed from the mid-1820s to the mid-1830s, the peak of the fur trade. Each spring and fall, several competing companies of trappers traversed the land, often spending the winter on the Snake River.

The introduction of the fur trade into Eastern Idaho altered the subsistence strategies for some Native American tribes, who both supported and opposed the trappers’ intrusion into the territory. This was a key transitional period for the Eastern Snake River Plain as Euro-Americans exploited, explored, and opened the area for later emigrant and westward expansion.

The land on the INL and the Eastern Snake River Plain came into contact with the fur trade out of necessity. Trappers only trapped some of the creeks and rivers on the Snake River Plain, as most beaver were found in the frigid creeks surrounding the plain. However, trappers had to navigate the plain and the Snake River at its center to reach these locations. The easiest way to cross the vast basalt plain was through the lands now managed by the INL. As trappers traveled between the Salmon River country or farther west and the mountains on the eastern side of the plain, they needed to cross at two locations. The first route was between the river valleys of the Big Lost River, Little Lost River, and sometimes Birch Creek and Fort Hall, with Big Southern Butte and the Big Lost River at the center. The second route was between the same northern river valleys and Henry’s Fork, with Camas Creek in the middle. Both routes crossed INL lands, and fur trappers often stopped along the banks of the Big Lost River to camp.

On the Eastern Snake River Plain, as with the rest of the Snake country, the fur trade peaked in the mid-1830s and left a stark visual record of an inhospitable landscape that fur trappers learned to navigate and survive. This knowledge was useful in establishing the geography, routes, and sustainability of the area for later Americans. Many of the routes utilized by the early explorers, fur trappers, and Euro-American emigrants were the trails of the Northern Shoshone and Bannock people.

Western Expansion

Goodale’s Cutoff

After more than ten years of traveling across southern Idaho on the Oregon Trail, emigrant wagon trains began to take a new route in 1852. Instead of journeying along the trail south of the Snake River, the wagons headed north from Fort Hall toward Big Southern Butte and the Big Lost River on what is now the Idaho National Laboratory (INL) Site. Turning west, the trail took the emigrants along the northern edge of Craters of the Moon National Monument and Preserve and onto the Camas Prairie, rejoining the old Oregon Trail near Mountain Home.

The emigrant trail followed a seasonal migration route across the Snake River Plain used by the Northern Shoshone and Bannock people to reach the Camas Prairie. Explorers and fur trappers began to use the route in the early 1800s. By 1854, John Jeffrey was promoting the trail to emigrants, along with his toll-ferry across the Snake River. Few traveled the cutoff until gold was discovered in Idaho in the early 1860s when Timothy Goodale reopened the cutoff to emigrants and miners. With the success of the gold mines, the route became an important part of a transportation network across southern Idaho, supporting communication, commerce, and settlement in the state before the railroad and later highways replaced the trail.

After crossing the Snake River to reach Goodale’s Cutoff, emigrants faced the most challenging section of the trail. With no water along the 40-mile trail across the desert, Webb Spring on the north side of Big Southern Butte was the closest source and an important landmark for emigrants. When water was scarce at the butte, wagon trains traveled across the present-day Idaho National Laboratory (INL) Site to the Big Lost River. Many emigrants found relief at the river, but not all. In late summer, wagon trains sometimes found the Big Lost River dry at first sight and continued upstream until the river ran again. By the 1880s, stage service along the route to Big Southern Butte included an improved road and a stage station, but the journey was still unpleasant for emigrants and stagecoaches.

Emigrants wrote about their experiences in diaries and journals as they traveled the overland trails and Goodale’s Cutoff. They recorded the hardships of the journey over the desert to find water, as well as their impressions of the unfamiliar volcanic landscape they encountered crossing the INL. The diaries and journals recall familiar day-to-day activities like cooking and cleaning on the trail and many documented the loss of loved ones during the journey west.

Homesteading and agriculture

Ranchers primarily used the northern portion of what is now INL, while homesteading and agriculture took place in the western and northeastern portions.

Most homesteaders who arrived in the late 1800s settled along the Big Lost River. The first permanent settlers arrived in 1878, and the first official water right claim was recorded in 1879. Many settlers moved into the area because of the Homestead Act of 1862, which allowed the head of a family to obtain 160 acres by meeting certain criteria, such as residing on the land and cultivating it for five consecutive years. The Desert Land Act of 1877 also encouraged settlement in the Big Lost River area by permitting families to acquire 640 acres if they could bring water to it.

Water was rare in the desert areas of the eastern Snake River Plain, and successful farming depended on homesteaders’ ability to obtain it.

With the passage of the Carey Land Act in 1894 and the Desert Reclamation Act in 1902, the federal government assisted homesteaders. The 1894 act set aside one million acres of public land in Idaho for homesteading, provided settlers participated in state-sponsored irrigation projects. The 1902 act provided the funding necessary to reclaim these arid and semi-arid acres.

Southeastern Idaho greatly benefited from this federal aid, and from 1905 to 1920, agricultural activity increased dramatically on land within and around INL’s present-day boundaries. Idaho Falls’ population quadrupled from approximately 1,262 in 1900 to 4,827 in 1910 due to the promise of irrigable land. Irrigation companies formed and, with federal financial backing, built several dams, including the Mackay Dam on the Big Lost River upstream of INL, and canal projects that brought much-needed water to homesteaders. The town of Powell, later named Pioneer, sprang up along the Oregon Short Line Railroad in the southwestern portion of the present-day INL site to supply locals with necessary goods and serve as a stock-shipping station.

Unfortunately, gross miscalculations of precipitation and water flow in the area, along with ignorance of the fractured bedrock strata and porous gravels of the Big Lost River, led to the failure and abandonment of most of these projects in the 1920s. Many small homesteads on and around present-day INL closed, although a few notable exceptions in the Mud Lake area to the east and far upstream in the Big Lost River Valley flourished. Many historic sites within INL boundaries represent these short-lived efforts to reclaim the high desert for agriculture.

Idaho Statehood

Mining and Transportation

During the 1860s through the 1880s, discoveries of gold and other precious metals in central Idaho attracted many miners, causing boomtowns to spring up in areas north and west of present-day INL boundaries. These mining booms in the mid- to late-1800s created a need for transportation systems between the newly established mining towns north of INL, such as Mackay and Leadore, and their supply stations in older towns like Idaho Falls to the east and Blackfoot to the south. Freighting and staging became major businesses, and several companies formed to meet the demand for mining equipment, passenger service, dry goods, and other supplies. Old wagon roads and trails quickly turned into stage and freight lines, and several new trails formed across the desert.

The Big Southern Butte, with its freshwater springs in the otherwise dry desert, served as a stop for nearly all stage, freight, and later rail lines. Charles Berryman, George Rogers, Joe Skelton, and Henry Leatherman, three of the earliest freighters to cross the desert from Idaho Falls and Blackfoot to Arco, all used the Big Southern Butte as a way station.

In the 1890s, another way station, the Powell Stage Station, was established along the banks of the Big Lost River, approximately two miles north of INL’s Radioactive Waste Management Complex. George W. Powell, the station’s proprietor, built a rock building with a store and post office and maintained the only known bridge crossing of the Big Lost River in the area.

The Birch Creek Stage Station, established as early as 1884, was located at the north end of INL, along the banks of Birch Creek. It served as a stopover for travelers and freighters heading to the mining camps in the Birch Creek and Salmon River valleys.

The completion of the Oregon Short Line Railroad between Blackfoot and Arco in 1901 ended the era of stage and freight lines in the area.

Many of the mining boom towns of the mid- to late-1800s folded when the surrounding mines did not meet productivity expectations. One last minor boom occurred in 1925 when gold was discovered in the Lost River sinks. However, the gold was in such small quantities that extraction was economically infeasible.

As transportation through the desert became more reliable, settlers arrived and began ranching in the northern reaches of present-day INL. By the early 1900s, sheep were common in the area and are still moved from pastures near the Big Southern Butte across the INL area to Howe. Many of the isolated historic sites within INL’s boundaries are remnants of small, temporary camps created by sheep and cattle drovers as they moved their stock through the region at the end of the 19th century.

Arco Naval Proving Ground

In 1942, the U.S. Navy started testing naval ordnance on what is now INL.

During World War II, the U.S. Naval Ordnance Plant was established in Pocatello, Idaho, to manufacture, assemble, and reline Nweapons. Nearly all the naval ship guns used by the Pacific Fleet were sent to the plant for relining. Before the guns could return for active duty, they needed to be test-fired. The Arco Naval Proving Ground (NPG) was established 60 miles northwest of Pocatello as a remote site to test the guns for combat readiness. It was one of only six such facilities in the U.S. and the only one capable of test-firing the Pacific Fleet’s 16-inch battleship guns.

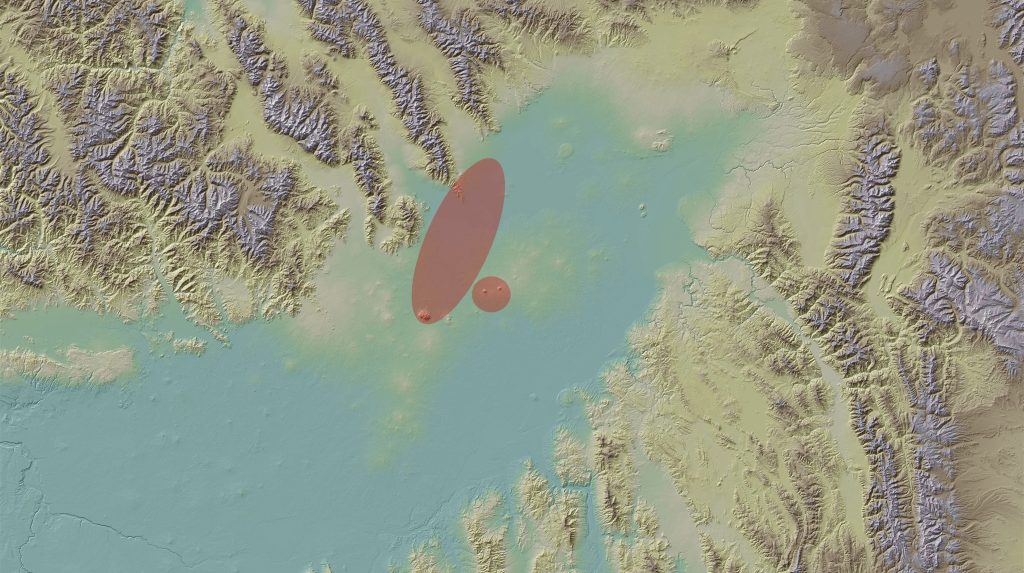

The Arco NPG covered 270 square miles and included operational support facilities and housing for military and civilian personnel. This infrastructure is mainly located at INL’s present-day Central Facilities Area (CFA) and also included rail lines, a 250-ton gantry crane, roads for gun transport, a concussion wall, downrange activities, various targets, spotting towers, and detonation areas. The Army Air Corps, flying out of Pocatello, set up two practice bombing ranges near the Arco NPG, one to the southwest of CFA and the other to the southeast.

United States Army Air Force– Bombing Ranges

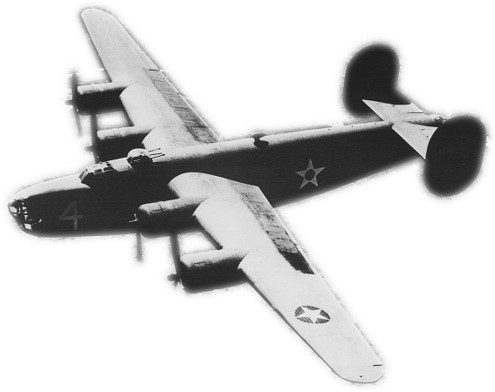

During WWII, the U.S. Navy shared land with the Pocatello Army Air Base for heavy bomber and fighter jet training, specifically B-17 and B-24 bombers and P-39 and P-47 fighters. The heavy bombers conducted practice runs at the Arco High Altitude Bombing Range and the Twin Buttes Bombing Range, both of which now overlap the INL. The Arco NPG and the two bombing ranges contributed to American victories in the Pacific during WWII.

After World War II, ordnance testing at the Arco NPG continued with explosives storage and transportation tests. Workers built structures, loaded them with explosives, and detonated them to test the effects on the structures and surrounding areas to determine safe storage of military ordnance. On August 29, 1945, they detonated 250,000 pounds of TNT, creating a mile-high smoke and dust cloud and a crater 15 feet deep. Another test on October 31, 1946, detonated 500,000 pounds of excess high explosives to determine the safe distance for explosive ordnance storage in the open. At the time, this was believed to be the world’s largest conventional ordnance explosion. Debris from this and other ordnance tests still remain on the INL landscape.

Between 1968 and 1970, during the Vietnam War, shots from massive 16-inch naval guns echoed through the Idaho desert again. A naval firing site, southwest of CFA, tested the battleship New Jersey’s armament. Since Atomic Energy Commission research facilities were scattered throughout the original downrange area of the Arco NPG, the guns tested at that time were aimed in the opposite direction. From the firing site a few miles south of CFA, the guns were aimed southward across uninhabited territory toward the Big Southern Butte. Craters still mark the butte’s northern flank.

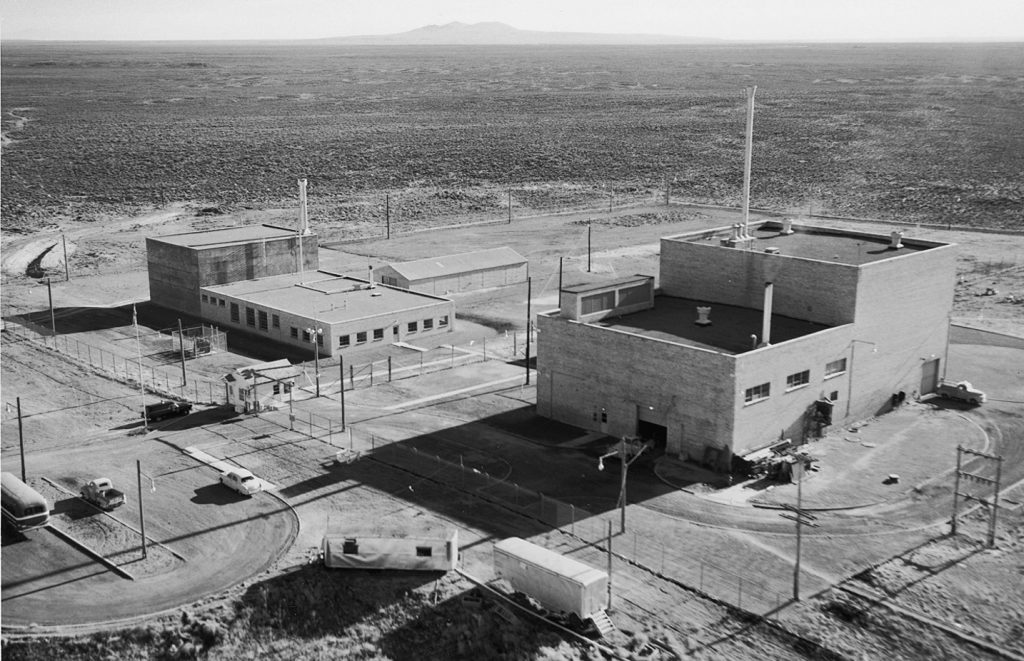

National Reactor Testing Station

In 1949, the Atomic Energy Commission designated 890 square miles of the Snake River Plain, including all of the former Arco NPG, as the National Reactor Testing Station (NRTS). Since then, scientists have built and tested 52 reactors on the site, which is now the INL. More information can be found on the INL History Page: https://inl.gov/history/

The Experimental Breeder Reactor I

The Experimental Breeder Reactor I (EBR-I) facility was constructed between 1949 and 1951 to house the namesake Experimental Breeder Reactor I. Designed by researchers at Argonne National Laboratory in Illinois and approved by the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC), EBR-I was the first nuclear testing facility to be constructed at the NRTS. Tasked with finding a peaceful use for atomic technology in the years after World War II, a team of scientists led by Walter Zinn set out to determine a reactor could create more fuel than it consumed and if electricity could be generated from nuclear energy. On 20 December 1951, the latter experiment proved successful when four light bulbs were illuminated at 1:23pm by electricity produced by EBR-I. The next day, atomic energy powered the whole facility. In the following years, EBR-I also proved that fissionable fuels could be bred in a reactor, that atomic energy could create a sufficient supply of electricity so as to be a commercially viable enterprise, and the bred plutonium could be safely used for fuel within a reactor. The reactor concluded operation in 1964 due to lack of assignments.

EBR-I Becomes a National Historic Landmark

On December 16, 1965, the Advisory Board on National Parks, Historic Sites, Buildings, and Monuments of the National Park Service recommended EBR-I eligible as a National Historic Landmark (NHL) for its “exceptional value in commemorating or illustrating the history of the United States.” AEC Director Glenn Seaborg made a formal application for the designation of EBR-I as a NHL, just three weeks later in January 1966. The application was approved in early February and a dedication ceremony was held August 1966, with President Lyndon B. Johnson presiding. The NHL boundary includes the EBR-I reactor, the reactor building – also referred to as EBR-I – and the guardhouse.

The reopening of EBR-I as a visitor center was initiated in 1972, but public access was not possible until the building was decontaminated. After securing funding, the decontamination and decommissioning work was completed satisfactorily and ahead of schedule on 13 June 1975. Since its decontamination, EBR-I has served as the Idaho National Laboratory’s only publicly accessible facility.

Historic Preservation Efforts at EBR-I

In 2023, Battelle Energy Alliance (BEA) Cultural Resource Management Office (CRMO) staff completed a preservation plan to document the current conditions of the EBR-I building and develop a preservation strategy to ensure the longevity of the property and continued safe access for visitors. This Plan addressed key issues specific to the maintenance of the EBR-I facility, including the history of the building; the existing conditions of the exterior envelope, basic structural systems, and interior spaces and features; and the historic significance and integrity of the building.

Additionally in 2023, BEA CRMO staff began a summer program – “Ask an Architectural Historian” – at EBR-I to engage with the public and increase awareness of historic preservation. The program continues to be held each summer. Want to visit EBR-I? Please visit https://inl.gov/ebr/ for more information.