Precontact History and Archaeology

Cultural Resources at INL

The ancestors of the Shoshone and Bannock people have occupied southern Idaho and the surrounding regions for thousands of years. This time span is referred to as the Precontact Period, which begins deep in time and ends when Euro-Americans arrived and began interacting with the first Americans, around 1805.

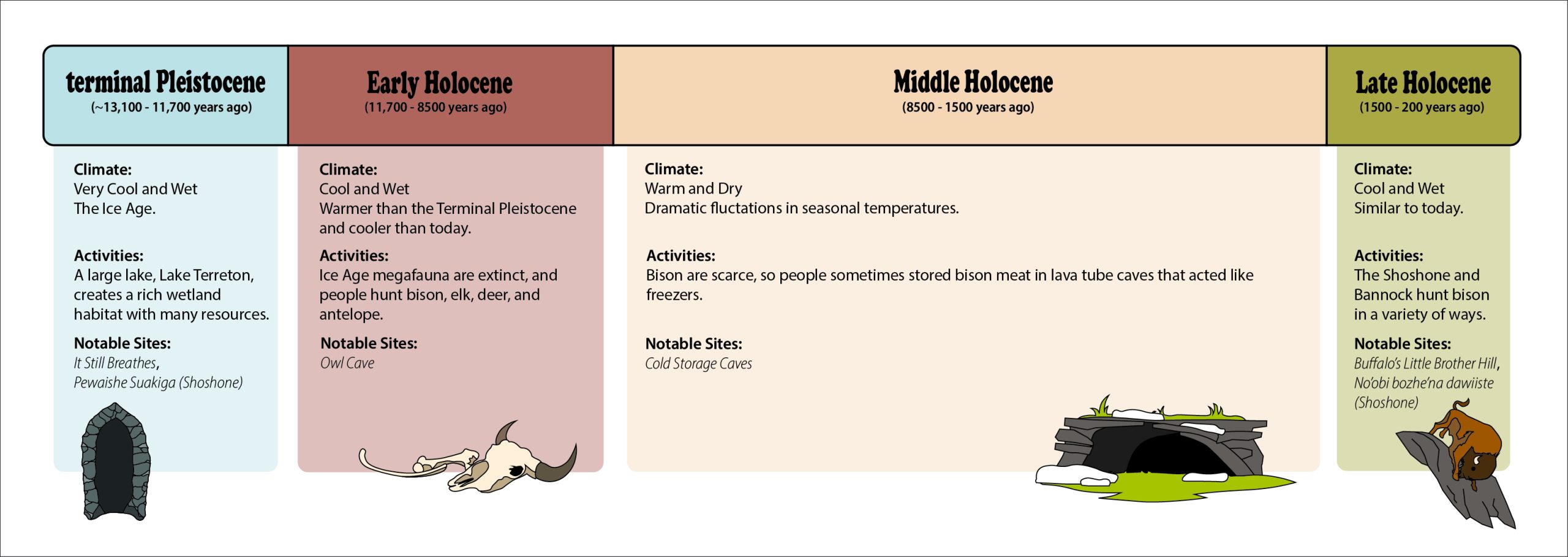

Archaeologists use geological time to describe the Precontact Period and to highlight significant environmental changes that impacted plants, animals and the humans that relied on these resources.

The Pleistocene Archaeological Record

Archaeological evidence shows that the ancestral Shoshone and Bannock people lived on the eastern Snake River Plain during the latter part of the Pleistocene epoch, or “Ice Age.” The environment was much cooler and wetter, but people adapted well to these conditions. Despite colder temperatures than today, game animals and plant resources were plentiful because glacial meltwater flooded the Pioneer Basin, forming a large lake, Lake Terreton, and creating rich wetland habitats.

These habitats were home to mammoths (Mammuthus columbi), camels (Camelops hesternus), horses (Equus sp.), muskoxes (Bootherium bombifrons) and their predators, including dire wolves (Canis dirus), short-faced cave bears (Arctodus sp.) and saber-toothed cats (Smilodon sp.).

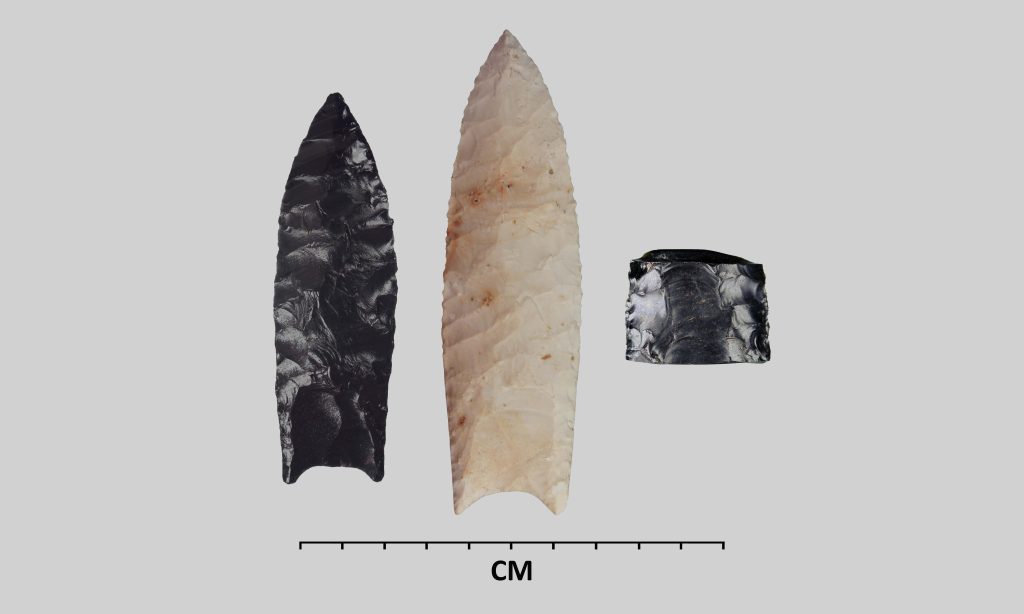

Although we haven’t found evidence that people hunted and killed these now-extinct animals in southeastern Idaho, Clovis and Folsom points, the same stone tools used to kill mammoths and extinct bison on the Great Plains, have been found in the Pioneer Basin. Clovis points are thought to be between 13,500 and 12,700 years old. Folsom technology seems to have replaced Clovis technology, appearing about 12,700 years ago. By roughly 12,000 years ago, other weapons replaced Folsom points as the climate warmed and large megafauna vanished.

Pewaishe Suakiga (Shoshone)/Pekwanishu songaga (Bannock), “It Still Breathes”: An unusual discovery in the desert west

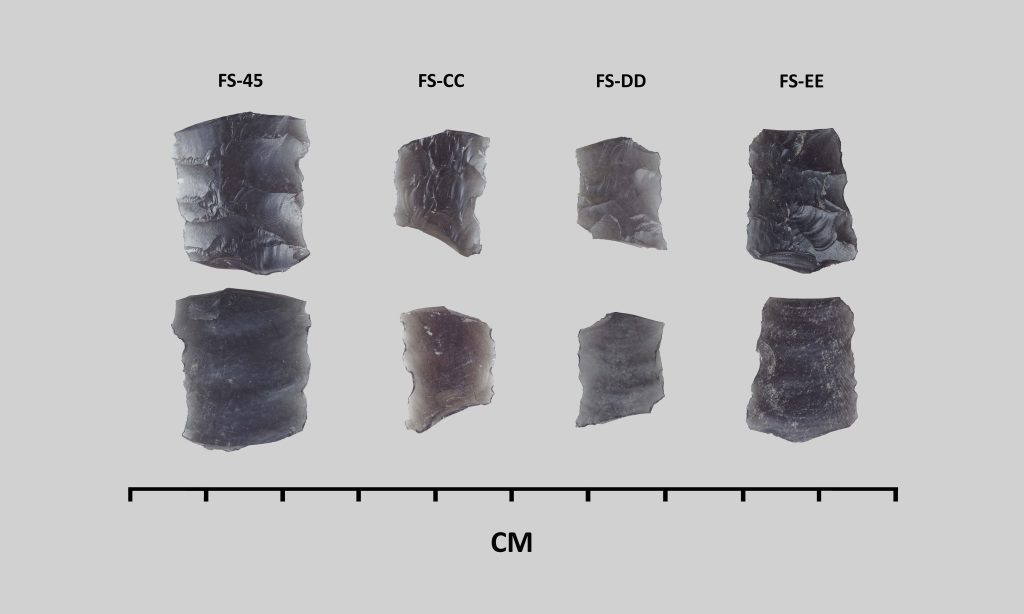

In the 1990s, archaeologists found Folsom points at a site now known as Pewaishe Suakiga, meaning “It Still Breathes.” The site is unusual because they also found “channel flakes” with the points. A channel flake is a byproduct of making a Folsom point. Although Folsom points are rare due to their great age, channel flakes are even rarer because natural processes easily destroy these fragile artifacts.

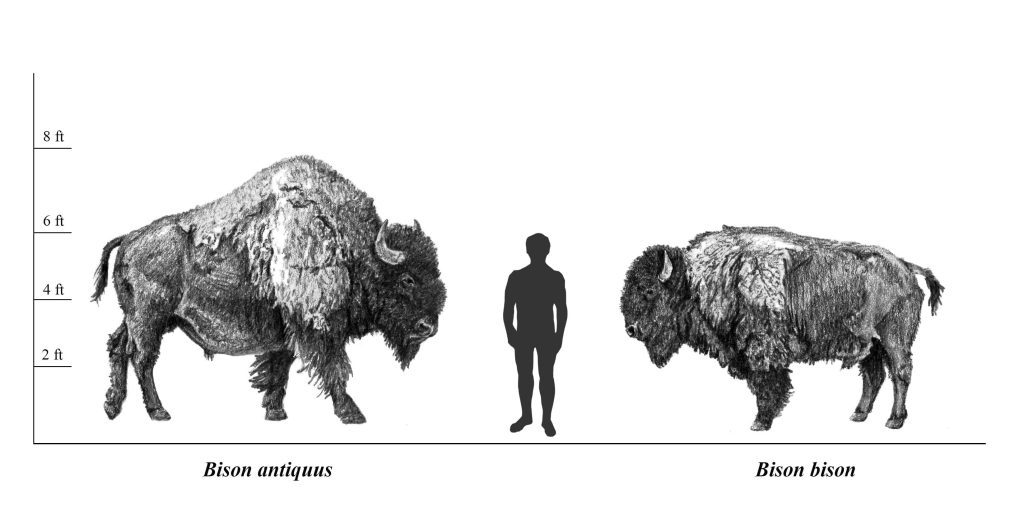

Folsom points are one of the most complicated stone tools ever crafted and require great skill to make. To prepare a Folsom point for attaching to a spear, one must remove a channel flake from both sides of the point. Archaeologists call the scar from the channel flake a “flute.” Although older Clovis points also have a flute on both sides, the Folsom flutes run nearly the full length of the point, making this tool very sturdy after being hafted. Folsom points appear to have served well as weapons for killing the ancient bison (Bison antiquus) on the Great Plains. The Bison antiquus was 25% larger than modern day bison, thus the Folsom point was an ideal hunting tool. INL archaeologists suspect that Folsom points served the same purpose in the Pioneer Basin, where herds of ancient bison roamed during the last 15,000 years of the Pleistocene epoch.

The Pewaishe Suakiga Folsom points, along with most of the Folsom points from the region, are made of obsidian, not chert or flint. The obsidian used to make these points came from nearby sources like Big Southern Butte. This is a significant discovery. Many archaeologists have argued that Clovis and Folsom hunters were very nomadic, never settling anywhere but following game great distances across vast regions. The fact that Folsom hunters in the Pioneer Basin knew exactly where to find local tool stone confirms the oral histories of the Shoshone and Bannock people. The eastern Snake River Plain has been their home for millennia.

With the onset of warmer, drier environmental conditions around 11,000 years ago, Lake Terreton retreated and ultimately disappeared. Although we still poorly understand the timing of megafauna extinctions in eastern Idaho, we know these extinctions are associated with the significant environmental changes that occurred as the Pleistocene epoch ended.

The Holocene Archaeological Record

Around 11,000 years ago, warmer, drier environmental trends emerged and prompted a new geological epoch called the Holocene. Climate studies show that the Holocene epoch has had both cool, wet periods and hot, dry periods. To capture these environmental changes and help archaeologists understand how people, animals, and plants responded, climatologists and archaeologists divided the Holocene epoch into three parts: the early Holocene, the middle Holocene, and the late Holocene (see timeline).

Owl Cave: An early Holocene bison kill on the eastern Snake River Plain

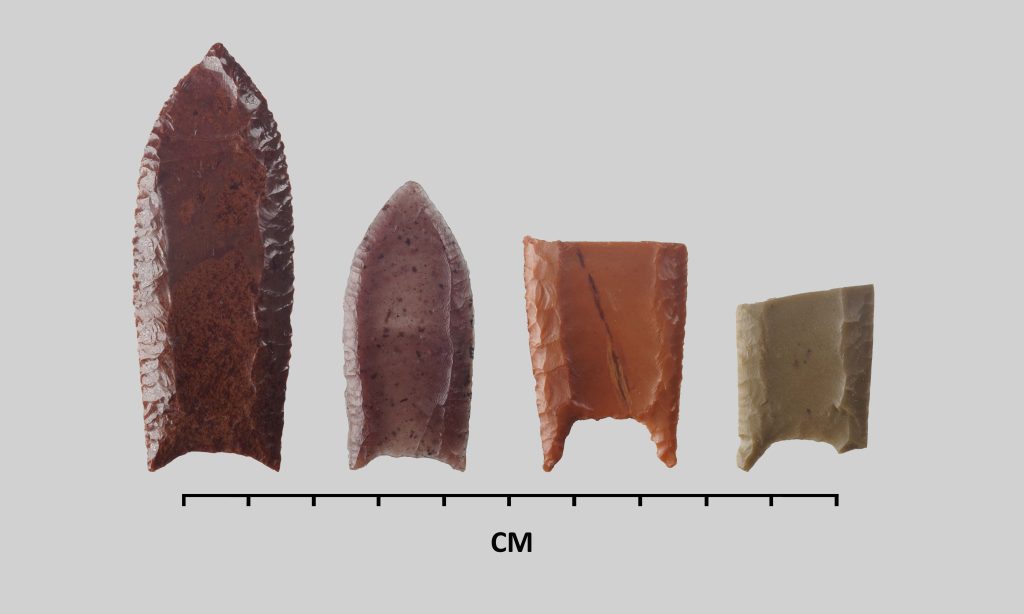

Despite the dramatic environmental changes at the end of the Pleistocene, the ancestors of the Shoshone and Bannock people adapted quickly and hunted animals that survived the late Pleistocene extinctions. Resident bison populations also adapted, like the modern bison, classified as Bison bison, from that of Bison antiquus during this period. Although smaller than Bison antiquus, modern bison are still formidable and dangerous to hunt.

In the late 1960s, researchers discovered a mass bison kill in a lava tube cave just east of the INL. This mass kill occurred about 9,000 years ago, after the onset of the Holocene epoch. Judging from the variation in the bones recovered from this ancient “bone bed,” the herd included very large bison within the size range of Bison antiquus, and smaller specimens appear to be Bison bison. This evidence shows that bison populations on the eastern Snake River Plain were adapting to changing conditions well into the early Holocene.

Roughly 100 bison may have been killed in Owl Cave during what appears to be a single event. Unlike the Folsom points from the Pioneer Basin, the obsidian and other stone tools associated with this kill came from much greater distances, suggesting that this was an organized, communal hunt involving many groups coming together. Researchers are investigating whether the kill occurred during the spring or fall. A fall kill involving a cow/calf herd would have provided plenty of rich, fatty meat over the winter. Early spring may seem an odd time for a bison kill because the meat would have been very lean, but other parts of a bison, including bone marrow, would have provided essential nutrients following a hard winter.

Cold storage during the middle Holocene

Around 7,500 years ago, with the onset of even warmer, drier conditions that mark the beginning of the middle Holocene, mass bison kills seem to have ceased. Bison herds on the eastern Snake River Plain likely became much smaller because the cool-season grasses typically available on the sagebrush steppe during wetter times would have greatly reduced during hot, dry periods.

The cataclysmic eruption of Mount Mazama in central Oregon about 7,700 years ago also marks the beginning of the middle Holocene. This eruption was one of the largest anywhere on Earth during the last 12,000 years. Southeastern Idaho, like much of western North America, was covered with a thick layer of ash. Archaeologists encountered the ash while excavating the sediments of Owl Cave. We still poorly understand how this eruption and the dark skies that followed may have affected the eastern Snake River Plain’s climate, plants, and animals.

Despite the hardships created by the hot, dry phases of the middle Holocene, the ancestors of the Shoshone and Bannock people adapted as always. They used the cold lava tube caves scattered across the eastern Snake River Plain to preserve a precious resource; bison.

Evidence from the seven known “cold storage caves” in the region shows that these sites were part of the expansive seasonal round and important to small, extended family groups that traveled across their territory each year to gather resources. However, hunting bison on foot, hauling them to dark caves, and carefully insulating meat and carcasses from warm air and carnivores, like grizzly bears and wolves, was likely very challenging.

When the climate was cool and moist and bison were plentiful, the ancestral Shoshone and Bannock people probably didn’t bother with the cold storage caves. Nevertheless, they likely handed down cave locations from generation to generation.

The Late Holocene Archaeological Record

Around 4,000 years ago, southern Idaho experienced a thousand-year span of cooler, wetter weather. However, by around 2,500 years ago, people were putting bison meat on ice again, indicating another dry spell that may have lasted several hundred years.

Another dry period occurred between 1,100 and 800 years ago. This dry phase on the eastern Snake River Plain is associated with what scientists call the Medieval Warm Period (MWP). The MWP caused long-term megadroughts and the collapse of agriculture in many parts of North America, including the complex civilizations in Chaco Canyon, New Mexico, and Cahokia, Illinois.

However, the ancestors of the Shoshone and Bannock people did not depend on horticulture or agriculture. They hunted and gathered resources during the MWP. We do not fully understand how this megadrought impacted the availability of water, plants, and animals in the Pioneer Basin. Researchers are still studying these impacts.

Teppi Muhave (Bannock)/Te´iya aika tempi pa´ayunde (Shoshone)

Teppi Muhave is one of the sites that may date to the MWP or soon afterward. The Bannock and Shoshone names for this site mean “Lookout for Animals and People”. Located on a high basalt pressure ridge overlooking a large, broad basin, this site provides a tremendous, long-distance view of the surrounding terrain. People constructed many rock walls on the ridgetop so they could “look out” without being seen. Women and children could stay hidden and safe at the seasonal base camp in sheltered areas at the base of the ridge.

A cooler, wetter climate seems to have returned around 700 years ago, a period referred to as the “Little Ice Age” or LIA. Just like the Medieval Warm Period, the “Little Ice Age” occurred throughout the Northern Hemisphere. On the Snake River Plain, the cooler, wetter climate of the LIA allowed cool-season grasses to thrive. When grasses thrive, bison herds flourish.

In the graph in the bottom right, note the significant change in temperature and precipitation that follows the Medieval Climatic Anomaly. Fur trappers’ journals from the early 1800s refer to the “thousands of bison” on the Snake River Plain, confirming that grass became plentiful during this time. As you can see in the graph, we also know that people never used the cold storage caves to store bison following the onset of the LIA. People may have abandoned bison storage simply because they didn’t need it anymore. It’s even possible that deeper portions of Lake Terreton refilled, providing wetland habitats once again.

No’obi bozhe’na dawiiste (Shoshone)

The site now called “Buffalo’s Little Brother Hill” served as a bison jump during the LIA. Like the bison jumps on the Great Plains, it features drive lanes extending from a large basin to several steep basalt cliffs where bison fell to their deaths.

Planning a successful bison jump takes a lot of effort. First, the bison herd needs to be large enough for a stampede, and there must be enough people to keep the bison moving in the right direction. Executing a bison jump is very dangerous. Because the lead bison can turn quickly, they must not see the cliff until the last moment. As the lead bison approach the cliff’s edge, it must be too late for them to react. The rest of the herd then pushes them over.

People used Buffalo’s Little Brother Hill repeatedly as a bison jump between 800 and 300 years ago when bison were plentiful on the Snake River Plain. However, by the late 1600s, jumps may have become unnecessary. The Shoshone and Bannock people had acquired horses from their sister tribe, the Comanche and quickly became skilled at hunting bison on horseback.