As the world gets wise to the threat of industrial cyber sabotage, Idaho State University is defining a curriculum to train a new generation of gatekeepers and guardians.

“We’re taking engineering technology students – mechanical, electrical, instrumentation, nuclear – and giving them industrial cybersecurity on top of that,” said Sean McBride, the program coordinator, who has been on the job full-time for four years under a joint appointment with INL. “By the time you graduate, you have hands-on experience with industrial systems, and you know how those systems can be attacked, and you’ve practiced the fundamentals of how to defend them. INL has been very involved in everything we have here,” he said.

During the program, students get hands-on training at keeping factories and power plants secure against malicious online intervention. Hackers are out there, and they have plenty of targets. The idea is that if students can learn cybersecurity protocols at the same time they are gaining their understanding of industrial processes, they’ll have a more integrated outlook when they go to work in the real world.

“I had no idea what industrial cybersecurity was all about. It was a real eye-opener,” said Jack Hall of Pocatello, who was due to earn his associate degree in May and plans to follow on for a bachelor’s. “This program here at ISU, as far as I know, it’s the only program of its kind in the country.”

Bridging the gap between information technology and operational technology is done with what’s called CCE: consequence-driven, cyber-informed engineering – an INL-developed methodology that McBride has incorporated into his curriculum. CCE is intended to provide utilities with clear steps to evaluate an organization’s most critical functions that must not fail. It then identifies the approach an attacker might take to sabotage critical systems and applies proven engineering protection strategies to reduce the risk. More formally, the methodology employs a consequence-based risk management approach to cybersecurity.

Hall said he spent his first two semesters in the lab, learning about processes and physics. “If you don’t understand the processes in an industrial plant, you won’t know how to protect it,” he said. The second two semesters were more cyber-focused, with a special emphasis on programmable logic controllers. “If hackers can change the control logic, they can do some real damage,” he said.

While headlines tend to focus on state-sponsored hacks, there are plenty of smaller actors looking for companies to extort with ransomware – shutting down a network and holding it hostage in return for payment. To prepare, companies need to operate on a “not if but when” basis and have people on the staff who can minimize the damage, McBride said.

Mark Jackson of Idaho Falls said he first heard about ISU’s program at a College of Eastern Idaho open house. Although his first interest was in instrumentation, as an industrial cybersecurity student, he has been learning about networking, risk management and assessment, asset inventories, and cyber events. He also plans to pursue a bachelor’s degree.

“We have a lot of employers who are looking for people with bachelor’s degrees,” McBride said. As word spreads about ISU’s program, the university has established ties with Rockwell Automation (the parent company of Allen-Bradley), Accenture (a consulting and processing services company), and West Yost Associates (a water engineering firm). Ties with INL remain strong, with students taking part in internships and taking positions after graduation.

ISU’s relationship with INL has existed for years, and as such, has formed the foundation of what is being called the Idaho Cyber Education Ecosystem, which includes all the state’s institutions of higher learning as well as the community colleges. After the Idaho Legislature approved bonds in 2017 to build the Cybercore Integration Center and the Collaborative Computing Center, a memorandum of understanding was executed the following year saying they would be used for joint research and education endeavors.

“ISU has particular strengths. They definitely have a hands-on approach,” said Eleanor Taylor, INL Cybercore program manager for Workforce Development and Community Partnerships. “What they’re doing is very necessary and very unique in the effort to develop a national industrial control systems cybersecurity talent pipeline.”

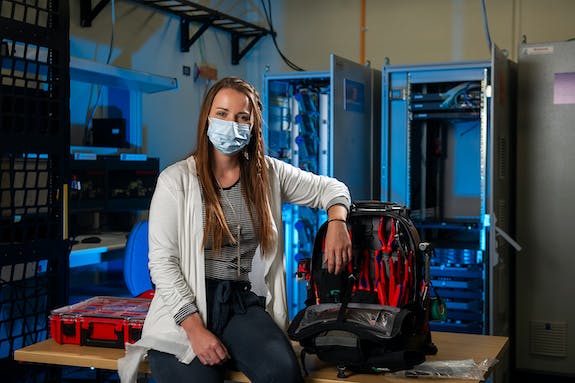

One ISU graduate who has stayed involved is Katy Fetzer, now a control systems cybersecurity analyst at the Cybercore Integration Center. “I think the program is really beneficial,” she said. “It helps students determine whatever path they might want to take, whether it’s industrial controls or risk management.”

In her case, Fetzer earned her associate degree in cybersecurity while pursuing bachelor’s degrees in applied science and criminology. “I really enjoy deciphering, understanding why an adversary might want to get into a system,” she said. She has frequently visited classes at ISU, offering insights and perhaps inspiration to students who want to investigate unique career paths.

Cybercore had three interns from ISU in 2020 and anticipates more in 2021. “It makes me hopeful,” Fetzer said. “I see the demand growing. That comes from awareness. Every day we see more and more scams, so many more attacks.”

Looking at job placement websites, McBride said he’s detected interest from employers that surprised him, including Post Consumer Brands and Walt Disney Co. “So much of their operations are built around these computer systems that they’re realizing, ‘Oh yeah, we need someone who can speak the language of both the plant professional as well as the cybersecurity professional,’” he said.

The value of qualified people shouldn’t be underestimated. While the pharmaceutical company Merck & Co. may be a household name today because of the COVID-19 pandemic and vaccine, McBride was talking about it with his students in 2018. That’s because the year prior, the company was hit by a ransomware attack called NotPetya.

The attack came from GRU, Russia’s military intelligence agency, and the real target was in Ukraine. NotPetya’s effects were felt worldwide, to the extent that Wired Magazine called it the most devastating cyberattack ever seen. As collateral damage, Merck alone saw roughly $300 million in lost information and crippled manufacturing capacity.

“I tell my students that if Merck had applied the principles we teach in this course, they could have saved $300 million,” McBride said.

As the program continues to grow, McBride is also working with INL to create a national Industrial Control Systems Cybersecurity Education and Training Community of Practice. This means building a network of people from industry, academia and government to focus on developing industrial cybersecurity educational materials and approaches.

The community includes universities such as Auburn, Clemson and Purdue, as well as the International Society of Automation. “They’re all uniting around the idea that industrial cybersecurity deserves special attention from educators,” McBride said.