Many hold fond memories of their first “real” car. That first car has stayed with Michael Vollmer and led to a hobby that has lasted more than 25 years.

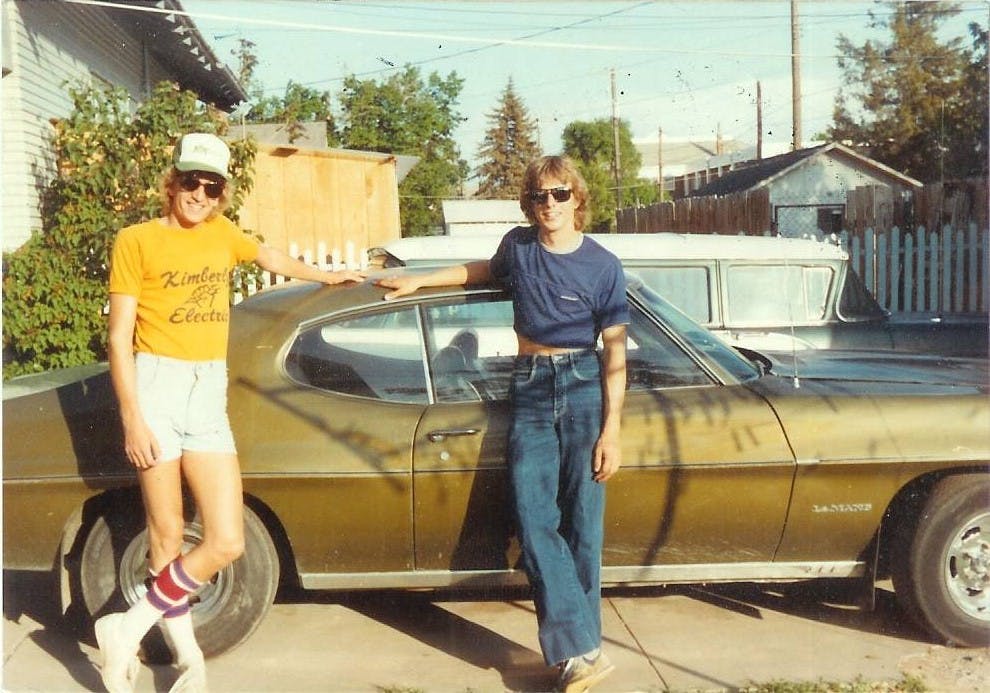

Vollmer still has the bright yellow 1972 Pontiac Lemans he bought for $600 in 1983. “This is my first car, and it’s been through so many changes,” he said. “I’ve beat the heck out of this car. I graduated high school in this car and even took this car on my honeymoon.”

Today, he’s modified the car to go 660 feet down an oiled speedway at 105 mph.

“This winter, I made 283 adjustments on this car,” Vollmer said as he walked around the Pontiac that was gutted for speed and now holds a V-8 engine he built to provide consistent performance on a short drag-racing track.

Vollmer is one of a handful of Idaho National Laboratory racers at the Sage Raceway, a popular venue in eastern Idaho. Vollmer’s commitment to fine-tuning the Lemans is reflected in his acute attention to detail recorded in the notebook kept in his custom furnished car trailer. Inside the graph papered lab book is the recorded history of his racing, starting with his first race on May 31, 1996.

The first page reads, “First race ever. Right out of the box. Cool temps, clear skies.”

His racing career has run parallel to his career at Idaho National Laboratory, which has also spanned more than 25 years. He started at the lab as an intern before moving to full-time work in 1991. He has spent the last 11 years as a counterintelligence specialist.

“My work relates to the protection of laboratory classified and sensitive programs, personnel, and assets from foreign intelligence collection, and international terrorist activities. The goal is to detect and deter trusted insiders who would engage in activities on behalf of a foreign intelligence service or foreign terrorist entity.”

In a way, his day job is not unlike the coordinated planning required to be the best on the racetrack as he reviews potential threats to his win. Before he even revs his engine, he’s measured wind speeds, the amount of dust blowing off freshly plowed fields, altitude density and even the humidity in the air. There is also a hodgepodge of cars and trucks to compete against, including Teslas, imports, street cars, motorcycles and even a pair of snow machines.

But make no mistake about it: Vollmer is a force to be reckoned with on the racetrack. Not only does he win a lot of races, but because he’s good at crunching available data and using that information to his advantage, he’s spectacular to watch. Vollmer is often out in front when the race lights move from red to green, and his competitors are left in a pillow of exhaust as racing fans cheers loudly over screaming engines and pumping pistons. It’s hard to miss his popularity with other racers and local fans, some whom come specifically to watch him race.

On race day, there is a white number written on the windshield of his car: 6.72. This was how fast Vollmer anticipated he would travel the 660 feet of track: 6 seconds, 720 milliseconds. Vollmer likes going fast, but more than that, he likes it when his calculations come together for the best possible outcome. He finds a deep satisfaction in solving the speed puzzle.

Vollmer supports other drivers and is quick to lend a hand or tool to improve anyone’s race day experience. This kind of collaborative team effort despite the solitary feel of the individual racer is mirrored in his work in as a counterintelligence officer at the lab.

“The laboratory leadership is very supportive of the counterintelligence mission and ensures we are integrated into the laboratory workflow processes – like briefings, travel safety and reporting matters of potential counterintelligence concern,” Vollmer said of the teamwork required to be successful in defending INL. “We appreciate all of our lab partners and the great concern many of them show for our mission. Without their due diligence, my job would be much more difficult.”

And while Vollmer worked on another racer’s truck parked next to his trailer at the speedway, his wife Jodi Vollmer said, “We’re all one big family out here. I love the camaraderie of the raceway.”

Vollmer looked up and smiled at Jodi.

He agrees.

Hobbies are fulfilling, and fulfilled people make more productive employees. Hobbies unearth hidden skills, alleviate stress, unite you with others, and improve quality of life — all things that will help you function better at work. See other stories about Idaho National Lab employees.