If you think archaeology is about retrieving golden trophies from snake-filled caves, Dr. Suzann Henrikson of Idaho National Laboratory’s Cultural Resources Management Office would like you to know it’s much more interesting than that.

May is Idaho Archaeology and Historic Preservation Month, a time for Henrikson and her colleagues to share with the public the work they do on the lab’s 890 square miles. If the “Lara Croft: Tomb Raider” film image of archaeology persists, it’s probably because archaeologists aren’t as good at sharing their stories with the public as they could be, she said.

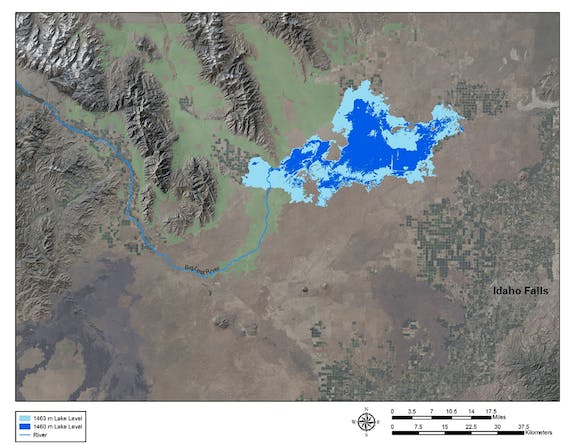

On the lab’s northern boundary lies what’s left of Lake Terreton, a large body of water fed by the glacial runoff at the end of the ice age, around 15,000 years ago. Some of the earliest human inhabitants of North America lived there, hunting huge mammals, most likely mammoth and extinct forms of bison. The projectile points scattered across the eastern Snake River Plain indicate these people were not tethered to the lakeshore. “Although Birch Creek and the Big Lost River now only run seasonally, these water courses were probably perennial back then,” Henrikson said.

What makes the research very compelling is that these people were most likely the forebears of the bands of Shoshone and Bannock people who now comprise the Shoshone-Bannock Tribes. “This really is their story,” she said. “I have no reason to believe their ancestors weren’t the first people here and the first bison hunters here.”

The tribes have their legends and stories, products of an oral tradition that stretches back centuries. Ultimately, collecting those stories, along with pictographs and petroglyphs, and matching them with the scientific findings is what will provide the most complete picture of what happened during the last 15,000 years, and what alterations were brought about by factors such as climate change and geological activity.

This is why when you see an arrowhead on the ground, you don’t pick it up. Where it is, it represents a data point. “When you remove an object from its context, it becomes useless,” Henrikson said. “If projectile point goes into someone’s shoebox, it’s a huge loss. Once that information is gone, it’s gone.”

INL’s vast area has been off limits to the public for nearly 70 years, which makes it an archaeological treasure. The land holds the information from 13,000 years of occupation by the Shoshone and Bannock people and their ancestors. Fur trappers began showing up in the early 19th century, followed by pioneers and homesteaders. In the first half of the 20th century, the land became a proving ground for the U.S. Navy, where warship gun barrels re-lined and re-rifled in Pocatello were brought to be tested. It was a bombing test range during World War II, and in 1949, the Atomic Energy Commission selected it as the site for the National Reactor Testing Station.

Archaeological studies on the eastern Snake River Plain date back to the 1930s. But in the 1950s, the same time the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) was building the National Reactor Testing Station (NRTS), archaeology underwent a revolution, with the focus shifting from the collection of artifacts to the study of people and how they survived over thousands of years on an ever-changing landscape.

Perhaps the most significant mid-century development, however, was the passage of the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, which said that federal agencies were responsible for managing archaeological resources and historic buildings on federal lands. “Protect and preserve” are at the heart of INL’s Cultural Resources Management Plan. “It’s a huge job to manage these resources,”’ Henrikson said.

Henrikson came to INL in 2016 from Burley, where she had been working for the U.S. Bureau of Land Management. She has spent her career studying the archaeology of the Great Basin, where large ice age lakes were attractive to the first people inhabiting the region. While lakeside settlements were common in the Basin and Range territory, she was surprised to discover that the archaeology surrounding Lake Terreton tells a different story.

“This is a totally new perspective,” she said. “The challenge for us is to explain why people used the landscape around Lake Terreton in a way that’s distinct from the rest of the desert West. We can look at the climate and the environment and gather data that will help us understand when the lake was at its maximum depth.”

Ultimately, the magic of the eastern Snake River Plain during the last gasps of the ice age may have been an abundance of surface water that extended far beyond the lake. Large mammals like mammoth and bison would have been everywhere on this rich landscape, making it an extremely attractive area for the ancestors of the Shoshone and Bannock people.

But it is a story of constant change. By 8,000 years ago, when the glaciers had disappeared, the archaeological record indicates that Lake Terreton evaporated and the water table dropped. In response, ancestors of the Shoshone and Bannock people began to use the entire Snake River Plain, including the open sagebrush steppe, where water would have only been available in seasonal meltwater ponds. To get across this region, it would have been critical to know exactly where these water catchments were located.

“I think it’s important for the Tribes,” said Larae Bill, Cultural Resources specialist for the Shoshone-Bannock Tribes Cultural Resources/Heritage Tribal Office Program. Her people, especially the elders, have special sensitivities about the land and what has happened to it in the past few hundred years. “It will help the scientific world to know we’ve been here for thousands and thousands of years and we need to protect and preserve our history,” Bill said.

Bill has handled cultural resources for the Tribes for close to 20 years. The relationship with INL has changed markedly, for the better. “They’re always asking for our perspective,” she said. “They’re very sensitive to our wish that anything they find be left on the ground, documented and photographed.”

Integrating the scientific record with the oral traditions is probably the hardest challenge. “With a lot of the elders, we have to be careful about what kind of information we want to give out,” she said.

Reaching out to a wider public, the Shoshone-Bannock Tribes are eager to tell their story. “I think (people) need to know that INL is not just this desolate desert landscape. It has a history that is really important to the Tribes.”