When it comes to convenience, reliability and performance, electric vehicles are fast approaching vehicles powered with conventional fuels. As a result, EVs are expected to make up a growing proportion of cars on U.S. highways during the next 20 years.

Much of this anticipated growth is due to recent advances in battery and charging technologies. Some cars with modern lithium-ion batteries can now drive between 230 and 330 miles on a single charge. Add next-generation charging technologies, and the so-called “range anxiety” that gives consumers pause when considering an EV purchase could soon disappear.

However, a new study on charging in cold temperatures suggests that industry and EV drivers still face charging challenges. The reason: cold temperatures impact the electrochemical reactions within the cell, and onboard battery management systems limit the charging rate to avoid damage to the battery.

The study was published online in July by Energy Policy journal. In it, researchers at Idaho National Laboratory looked at data from a fleet of EV taxis in New York City and found that charging times increased as temperatures dropped. The study will appear in a future issue of the journal Energy Policy.

“Battery researchers have known about the degradation of charging efficiency under cold temperatures for a long time,” said Yutaka Motoaki, an EV researcher with INL’s Advanced Vehicles research group.

But most of the current knowledge comes from experiments with smaller batteries in the lab, not data from large, electric vehicle batteries in real-world conditions. Further, EV manufacturers often provide consumers with only rough estimates of charging times, and they typically do not specify the range of conditions for which those estimates apply.

“We wanted to ask the question: What is the temperature effect on that battery pack?” Motoaki said. “What is the effect of degradation of charging efficiency on vehicle performance?”

Motoaki and his colleagues analyzed data from a fleet of Nissan Leafs operated as taxis over roughly 500 Direct Current Fast Charge (DCFC) events. Temperatures for the charging events ranged from 15 to 103 degrees Fahrenheit.

The researchers found that charging times increased significantly when the weather got cold. When an EV battery was charged at 77 degrees, a DCFC charger might charge a battery to 80 percent capacity in 30 minutes. But at 32 degrees, the battery’s state of charge was 36 percent less after the same amount of time.

And the more the temperature dropped, the longer it took to charge the battery. Under the coldest conditions, the rate of charging was roughly three times slower than at warmer temperatures.

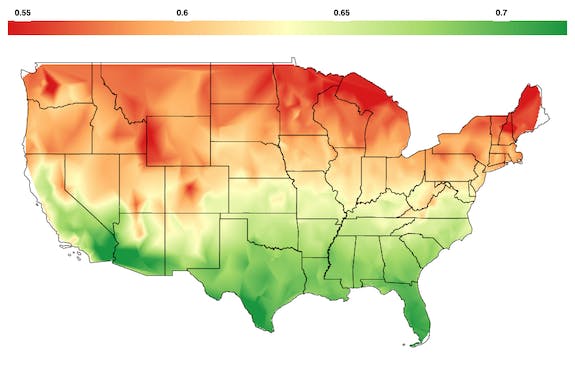

Motoaki and his colleagues used the data to create a map showing regions of the country where EV owners might experience longer charging times due to cold temperatures. As expected, high elevation regions and the northernmost parts of the country were more likely to be identified as places where cold temperatures could most affect charging times.

It’s important to note that cold weather would only impact EV drivers under specific circumstances, Motoaki said. For instance, people who charge their EVs in a warm garage and use their EVs for commuting within the range of their battery might not experience much inconvenience. Decreased fuel economy in cold weather is also a well-known phenomenon with gasoline and diesel-powered vehicles.

But time spent charging in cold temperatures could make a big difference for a taxi driver, since every minute spent charging a vehicle is a minute the driver is not making money.

The impacts of cold on EV battery charging times could be especially important for commercial vehicles that run on schedules, such as buses. In those instances, variable EV charging times could throw off the schedule or require heated spaces for charging.

Likewise, that extra charging time could inconvenience private EV drivers on long trips or people who live in apartments and don’t have access to chargers. More affordable EVs with smaller batteries that need to be charged more often might also pose more challenges in the cold.

“There’s a lot of uncertainty about what the vehicle owner’s experience would be if they drive the vehicle in Maine or Michigan,” Motoaki said.

The research poses questions not only for EV customers, but also for utilities and charging infrastructure providers. For instance, the location or abundance of charging infrastructure may need to be different in colder climates, and electric utilities might see electricity use vary as the seasons change.

Motoaki said further research is needed. The current study relies on a single type of electric vehicle, the Nissan Leaf, and a single type of charging system, 50-kW DCFC. Further, the data only included charging events less than 60 minutes long.

Funding was provided by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Vehicle Technologies Office (VTO).